Visham bhimull,

National Council of Indian Culture

Trinidad and Tobago

Abstract

__________________________________

Much of the colonial Indian diaspora, like India, have recognized Modern Stand- ard Hindi (MSH) as the authoritative form of the Hindustani language. The nation- alistic move by India to adopt the Khaṛī Bolī vernacular of Delhi as the standard of Hindustani seemed to have been mirrored in the international Indian diaspora. In Trinidad & Tobago (T&T), despite English being the of cial language and Trinidad English Creole being the lingua franca, MSH is still taught within the community of the Indian diaspora. These efforts are in an attempt to retain any manner or form of an ancestral language of this community for the purpose of being an ethnic language that ful lls the role of cultural expression and identity. Despite this MSH only ful lls a role of communication in a very small portion of the diaspora com- munity that comprises postcolonial Indian immigrants.

However, the language and culture that came with indentured Indian immigrants during the colonial period 1845-1917 came from a time in India when a different philosophy and linguistic situation prevailed. The language that comprised their expression and philosophical understanding came from a different literary era than MSH. Thus, a problem is presented to the diaspora in the search for their identity when they look towards present day India for answers.

If we closely examine Trinidad Hindustani as one of the vernaculars of the Hin- dustani of the international colonial Indian diaspora, it becomes clear that this language, apart from being one that belongs to a completely different literary era from MSH, it may be a different language from MSH altogether.

This paper analytically examines the various forms of expressions Trinidad Hin- dustani, e.g. storytelling, speech conversation, proverbs, and songs. In doing so, the peculiarities of the language are highlighted to bring an appreciation of how it best suits the unique culture of the colonial Indian diaspora of T&T. Indeed, MSH has served as a substitute for this language as, unlike Trinidad Hindustani, it is well studied, documented and has published materials from which one can learn it. However, it comes from an Indian nationalistic perspective which differs from the unique Uttar Pradesh/Bihar culture brought by indentured Indians. It is hoped

that this research will bring a renewed view of the Hindustani of the diaspora and would emphasize the need for documentation of the various forms of expression of this language, for the purpose of propagation of the unique cultural identity of the colonial Indian diaspora.

Key words: Caribbean Hindustani, Hindustani, Hindi, Trinidad Bhojpuri, Trinidad Hindi, Trinidad, Hindustani, Language, Culture, Overseas Hindi, chutney Music.

Résumé

________________________________

Une grande partie de la diaspora indienne de l’époque coloniale, ainsi que l’Inde, a reconnu l’hindi standard moderne (MSH) comme modèle authentique pour la langue hindoustani. Cette décision de l’Inde d’adopter le Khari Boli, langue ver- naculaire de Delhi, comme le standard de l’hindoustani semble se re éter dans la diaspora indienne internationale. À Trinidad et Tobago (T&T), malgré que l’anglais soit la langue of cielle et que le créole à base anglaise de Trinidad soit la « lingua franca », le MSH est toujours enseigné dans la communauté de la diaspora indienne. Cependant, la langue et la culture qui arrivèrent avec les travailleurs engagés indiens pendant la période coloniale 1845-1917 venaient d’une époque où une philo- sophie et une situation linguistique différentes prévalaient en Inde. Par conséquent, un problème se pose à la diaspora en recherche d’identité lorsqu’elle se tourne vers l’Inde actuelle pour obtenir des réponses.

Ce document analyse les différentes formes d’expression de l’hindoustani de Trinidad et met en lumière les particularités de la langue a n de montrer com- ment elles s’adaptent au mieux à la culture unique de la diaspora indienne de T&T. Bien sûr, le MSH a servi de remplaçant car, contrairement à l’hindoustani de Tri- nidad, il est bien étudié, documenté et de nombreuses publications permettent de l’apprendre. Toutefois, il correspond à une perspective nationale indienne qui est différente de la culture propre à l’Uttar Pradesh/Bihar apportée par les travailleurs engagés indiens. Nous espérons que cette recherche suscitera une approche renou- velée de l’hindoustani de la diaspora et soulignera le besoin de documentation sur les différentes formes d’expression de cette langue, a n d’assurer la diffusion de cette identité culturelle unique de la diaspora indienne de l’époque coloniale.

Mots-clés : hindoustani caribéen, hindoustani, hindi, bhojpuri trinidadien, hindi trinidadien, hindoustani, langue, culture, hindi d’outremer, musique chutney.

The terms Hindī and Hindustānī present a conundrum, not only to the colonial Indian diaspora, but to the nation of present day India itself. In the time of Amīr Khusrow, the renowned Su mystic and poet of the 13th-14th century AD, the adjective Hindī, or more often Hindavī (Hinduī), was often used. It was derived from the Persian noun “Hind” which is a cognate for the word “Sindh” the Sanskrit name for the Indus River. After the Islamic conquest of the Indian subcontinent, the adjective Hindavī was used by the Mughal aristocracy to describe the people, culture and language of their new empire in the land beyond the Indus River (amrit 1984). Naturally, during the time of the Mughal empire, the language of the Hindūs, Hindavī, was in direct contact with the heavily Arabicized Persian of the Muslim ruling class, and the reciprocity of in uence was indespensible (bahri 1960). Out of this interaction, was metamorphosed a language, that was referred to as Hindustānī by the British during their decades of westward conquest of Hindustān. In fact, the word “Hindustānī” was another adjective, this time a designation by the British, for anything of, or from Hindustān (The Place of the Hindūs). This language that was encountered by the British as the lingua franca on the North Indian subcontinent during the 18th-19th century AD, had different designations in the various strata of society. In the Mughal court it was called Rextā (mixed language), in the army it was called Urdū-Ē-Zabān (the language of the camp), and among the hoi polloi it was known as Hindustānī, the language of the people of Hindustān.

During the period of the westward British conquest of Hindustān, from Calcutta to Delhi, slavery was abolished. This resulted in the loss of cheap labor on the agricultural estates of many European colonies all over the world. As the British were gradually gaining control over Hindustān, they also gained control of the human resource in this slowly expanding new colony. The use of Indians as a cheap source of labor was an all too ingenious idea to ll the void that was left on the estates by the freedom of African slaves. During the period of 1833-1920, about 3.5 million Indians emigrated from Hindustān, under a contract system of Indentureship, to work on the agricultural estates in European colonies worldwide. The places of immigration included Mauritius, Fiji, South Africa, Suriname, Guyana and the Caribbean. This exodus of Indian emigrants from the South Asian subcontinent saw the transplantation of a resilient ancient culture and its dynamic language, that have endured even to today on these erstwhile colonies.

The pattern of recruitment that was in uenced by the westward move of the British was rather interesting. This pattern was evident in the lan- guage spoken by the Indentured Laborers and their descendants. In all the colonies, the majority of laborers referred to the language they spoke as Hindustānī. However, despite being mutually intelligible, the variety of Plantation Hindustānī that developed on each estate did differ to some extent. In addition to being in uenced by unique circumstances on each colony, this was also largely due to the fact that, earlier on, in the indentureship period, the British was only limited to recruits from south and west Bihār. Later, as the empire expanded westward, recruits began also being sourced from eastern and central United Provinces (modern Uttar Pradesh or U.P.). Hence, the Hindustānī spoken on the estates, Plantation Hindustānī, in places where laborers were brought earlier during indentureship, like Mauritius, Guyana,and Trinidad, had a heavier Bihārī avor. The colonies that received laborers later on, like Suriname and Fiji, had a Plantation Hindustānī of the U.P. style. East Indian indentureship in Trinidad lasted from 1845 to 1917. During that period, 147,592 Indian immigrants were brought to the shores of Trinidad. The majority of emigrants left from the port of Calcutta, the then British capital of Hindustān. Hugh Tinker reports that, from 1845 to 1860, many recruits comprised the Hill Coolies of the Chota Nagpur Plateau, formally part of the state of Bihār. A small number of recruits left from the southern part of Madras (mohan 1978). As the British expanded to the west, recruits were then sourced from the Gangetic plains. This started with western Bihār and then expanded into eastern and central UP. Hindustānī was the language

the majority claimed to have spoken.

Here, the conundrum rears its ugly head, creating fodder for misrepresenta-

tion. In modern day India, the term Hindustānī refers to a pluricentric lan- guage with two of cial standard forms, Modern Standard Hindi (MSH) and Modern Standard Urdu (MSU). These terms only consolidated after the parti- tion of Hindustān into India and Pakistan, and the declaration of both countries being separate independent nations in 1947. This would have been roughly a century after Indian indentureship started in Trinidad. From this modern de – nition of the term Hindustānī, one can infer that Plantation Hindustānī or the Hindustānī of the diaspora are just dialects of MSH. In fact, in modern times, MSH is seen to be the formal and authoritative vernacular of Hindustānī, the shining glory and bearer of Indian national cultural heritage. On the other hand, the Hindustānī varieties of the diaspora, like Trinidad Hindustānī, are viewed as broken and corrupted forms of MSH and exist as ickering ames on the verge of being extinguished. However, MSH only began reaching its pinnacle as the standard variety of Hindustānī about thirty years after the commencement of Indentureship. This fact calls into question the notion that the various varieties of Hindustānī in the diaspora are derived from MSH (rai 1984). Interestingly, in T&T, the literature handed down from the indentured immigrants to their descendants was not verses in MSH. In Trinidad, ever popular and alive are the verses of Tulsīdās’ Rāmcharitramānas in Avadhi, the Kṛṣnā poems of Surdās and Mīrā Bai in BrajBhāṣā, and the mystic Bhōjpurī compositions of Kabīr. These literary works date back to the Bhakti Movement of India around the 14th-17th century AD and represent earlier literary stand- ards of Hindustānī. Around that era, the vernacular of MSH was hardly cul- tivated as a literary language. This means that the linguistic situation in the colony of Hindustān during Indentureship was different from present day India. The term Hindustānī, may not have had the same de nition during that period, as the references of the standard vernacular of the language would have been different. The communal con ict which lead to the Partition of India and Pakistan in 1947, thirty years after Indentureship ended, involved much change in the religious and political ideology and philosophy in Hindustān. This change was represented in many facets in Indian expression, but one of the aspects in which it was most evident was the language.

The vernacular known as MSH was actually derived from the dialect of Hindustānī in and around the capital of New Delhi, an area in the proximity to the seat of power, both of the Mughal and the British Empires. This ver- nacular is known as Khaṛī Bōlī (established speech). Its rise to power is a rather complex story. Straddling its stream of development the two standards. MSH on one end and MSU on the other. Their relative centers of gravity being the Hindū community and Islamic community respectively. The evolutions of these two varieties as the standard registers of Hindustānī in the modern times, was heavily in uenced by the direction of the expansion of the British sovereignty and their imperial policy of “divide and rule”. However, it is noteworthy at this point to mention that Khaṛī Bōlī was hardly cultivated as written language during the medieval period. In fact, poetry in Khaṛī Bōlī did not appear until the last quarter of the 19th century. Before the rise of Khaṛī Bōlī, the literary dialects of Hindī were the ones adopted by the Bhakti saints: BrajBhāṣā (Kṛṣhnā devotees), Avadhī (adopted by Rāma devotees) and Maithilī (Vaiṣṇavaites of Bihār) (bahri 1960). The prime style of literary Hindustānī from the late fteenth century onwards was the western variety of Braj Bhaṣā from the Braj area to the south east of Delhi. These related the story of the escapades and adventures of the Hindū mythological gure Kṛṣhnā. It was not until the closing decades of the 19th century that Braj Bhaṣā, and not the neighbouring Khaṛī Bōlī, was meant by the designation of the term “Hindī” Patronage towards its cultivation as a literary standard was received by the local Mughal capital of Agra in this Braj area. More easterly was the Mughal capital of Lucknow in the Avadh region, the location of the Rāma myth, that gave patronage to the eastern variety of Hindustānī known as Avadhī. In this vernacular, was written the Rāmacharitramānas of the 16th century poet Tulsīdās, which is still regarded as forming the crowning glory of the whole of Hindī literature (ShackLe & SneLL 1990). The conquest by the British from Calcutta in the east to Delhi in the west over the 18th-20th Centuries did much to in uence the linguistic situation in India. The standards of BrajBhaṣā and Avadhī of the old Mughal capitals were superseded by the Khaṛī Bōlī dialect of Delhi, the new Capital of the British Raj from 1911 onwards. The turning point was after the establishment of the Fort William College by the British at Calcutta in 1800 to impart some knowledge of Indian languages to British of cials and young servants of the British East India Company. Around this time, prose works neither existed in Hindī nor Urdū. Neither varieties had prose traditions of any importance (kinG 1994). At this institution, it is said that the genesis of writings in Khaṛī Bōlī took place, and the rst important expressions of differentiation of the two variants of this vernacular, Hindī and Urdū also began here (kinG 1994). The drive towards this change was also fue- led by the replacement of Persian in the courts of justice by provincial stand- ard vernaculars. This meant that from the start of Indentureship, KhaṛīBōlī would have started its climb towards becoming an authoritative standard. However, it only reached respectability in full during the 1920’s (kinG 1994), some years after Indentureship ended. Because of this lack of antiquity in Khaṛī Bōl īHindī’s literary tradition, supporters and historians of MSH of the 19th and 20th centuries include the older literary traditions of BrajBhaṣā and Avadhī, and other regional standards in the discussion of “Hindī literature” of the more distant past. However, when discussing the literature of more recent and the present, they largely ignore these other traditions in favor of Khaṛī Bōlī. Thus, the myth of the antiquity of “Hindī” literature masks the reality that Khaṛī Bōlī literature lagged far behind from the vernaculars understood to be standard varieties of Hindustānī by the indentured Indian immigrants.

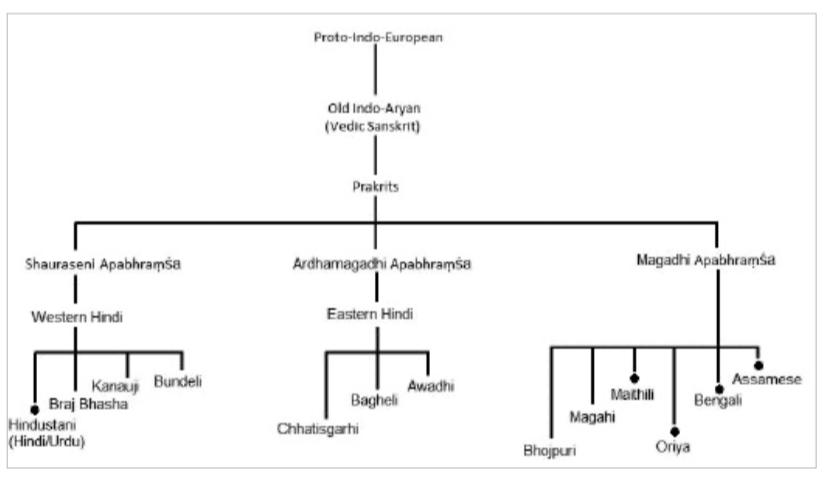

We can now make the statement that the Hindustānī spoken by East Indian indentured laborers belonged to a time when a dynamic linguistic change was taking place in the former British colony of Hindustān. It would follow that, the understanding of the linguistic term Hindustānī, handed down by the laborers to their descendants in the present day Indian diaspora, as in erstwhile colonies like Trinidad, would have been one from that pre-parti- tion linguistic situation in Hindustān. During the period of Indentureship in Trinidad, the Indians recruited spoke a fragmented spread of dialects of a language they called Hindustānī. To get a better understanding of the spread of vernaculars they spoke, and which ones mostly contributed and in uenced the Hindustānī that was developed on the estates (Plantation Hindustānī), we must now look, even more closely, at the areas in Hindustān from where they were recruited. According to Tinker, in the earlier part of Indentureship (1845-1860) they were recruited mostly from Hazārībāgh and Choṭānāgpur of the Chota Nagpur Plateau, formerly the southwestern part of Bihār. These Hill Coolies spoke mostly Nagpuriā (Sadani Bhōjpūrī) and some also spoke various tribal languages of the Astro-Asiatic language family. There were also a few untouchables who departed from Madras and spoke the Dravidian language of Tamil. However, from about 1857, as the British expanded west- wards, recruits were sourced from the Gangetic plains in the areas of western Bihār and eastern UP. From Bihār, these areas included: Muzaffarpur, Paṭnā, Gayā, Champāran, Śahabād, Sāran and Darbhangā. From U.P. these areas included: Gōrakhpur, Basti, Gōndā, Fyzābād, Jaunpur, Banāras, Āzamghar, Ghāzīpur and Balliā. The spread of the vernaculars of Hindustānī over these recruitment areas are better illustrated in Table 1.

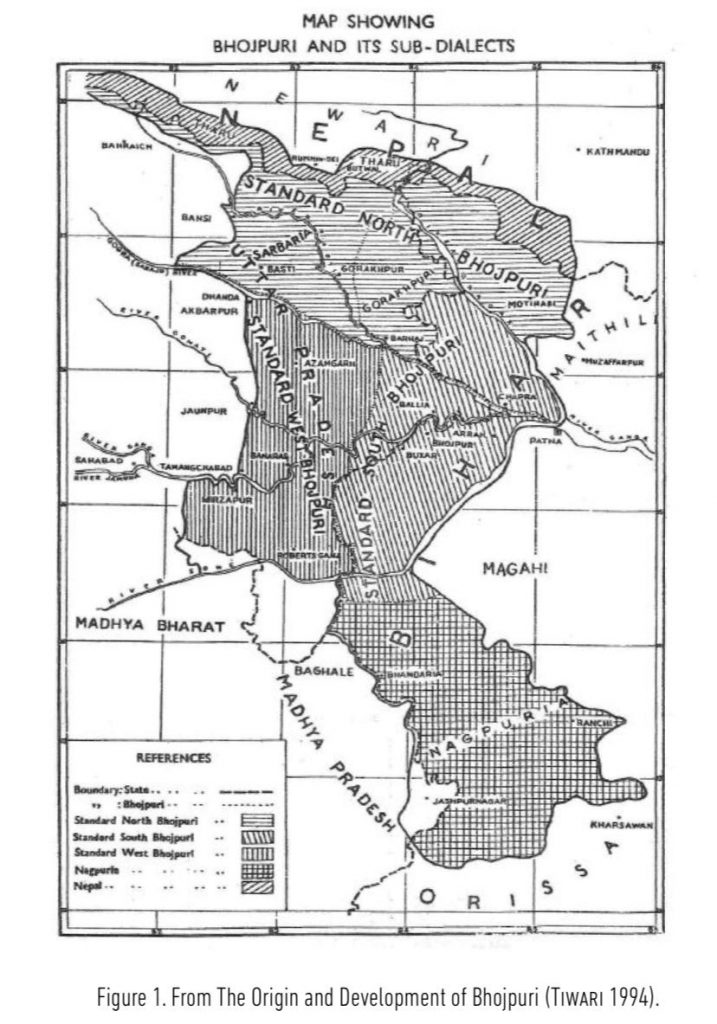

In T&T, there are no comprehensive accounts of the languages brought to Trinidad by the Indian indentured laborers (mohan 1978). To conduct any inquiry into this matter would prove to be very dif cult for two major reasons. Firstly, there is no substantial record of the languages to give a clear picture of vernaculars of Hindustānī brought by the indentured laborers. Secondly, as proven above, indentureship lasted about eight decades during a period when the South Asian subcontinent was going through dramatic linguistic change. Thus, the vernaculars of Hindustānī brought to Trinidad over that period, would have been at different stages of the language evolution and development. The data clearly points to the fact that the majority of Indian immigrants to Trinidad were native speakers of various dialects of Bhōjpurī. This is not

a surprising fact, as the areas where most of the Indians were recruited from was the Bhōjpurī speaking area of North East India: the western part of Bihār, the eastern part of U.P. and the southern, or Rānchī plateau of ChōṭāNāgpur. This linguistic area is demonstrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. From The Origin and Development of Bhojpuri (Tiwari 1994).

The Bhōjpurī brought to Trinidad was not particularly homogenous, since laborers were recruited from many different parts of the Bhōjpurī speaking territory. The Bhōjpurī brought from the subcontinent was an atomized spread of peasant dialects. The preponderance of Bhōjpurī speakers among the Indian indentured laborers taken to Trinidad is evident, not just from an examination of the areas from which the recruits were drawn for emigration, but also from the striking similarities between this variety of Hindustānī widely spoken in Trinidad and the different varieties of Bhōjpurī spoken in India. However, as can be seen from Table 1, Bhōjpurī was not the only Indic language taken

to Trinidad during this period. There were some recruits from areas of U.P. and Bihār which were directly contiguous to the Bhōjpurī speaking territory, which resulted in smaller groups of Avadhī, Magahī and Maithilī speakers. There is also anecdotal evidence that these languages were once spoken in Trinidad, as well as languages from further a eld, such as Bengali, Nepali and Telugu. Similarly, the immigrants from Madras brought with Tamil other Dravidian languages of south India (mohan 1978). The fact that Bhōjpurī was the largest group of regional vernaculars brought to Trinidad from Hindustān, meant it formed the “critical mass” that could make it a reasonable choice as a link language (mohan n.d.). Its dominance resulted in these various village dialects of Bhōjpurī crystallizing as the lingua franca of the Trinidadian Indian diaspora with the gradual disappearance of other vernaculars of Hindustānī brought by smaller groups of laborers from other regions outside the Bhōjpurī area (motiLaL 1885). Tamil was the only other Indian language that survived to some extent due to the signi cant numbers recruited from the untouchable community in Tamil Nadu (mohan n.d.). But even this small community assimilated Bhōjpurī as a necessity for communication with the rest of the diaspora. A new community had now come into existence, centered around Bhōjpurī that linked and identi ed the community. Bhōjpurī, was thus the vernacular on which Trinidadian Plantation Hindustānī had its foundation.

Bhōjpurī, in fact, found new life in Trinidad and elsewhere in the world through indentureship. As we saw before indentureship began shortly after Khaṛī Bōlī began its ascent towards becoming the standard Hindustānī. Around that time, Bhōjpurī was not a language with a center of gravity.

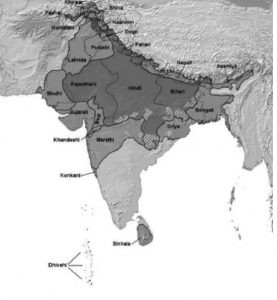

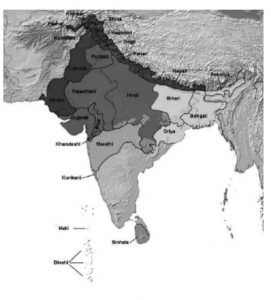

Figure 2. The Hindi Belt or region where the varieties of Hindi in the broadest sense are spoken Source: Hindi Bealt; Wikipedia.

Literary expression and political power were, by now, both in KhaṛīBōlī, the rst indication that this vernacular was MSH. By the time indentureship began, Bhōjpurī was already “colonized” by MSH, rendered submissive and menial. It was a language stunted and unable to grow as it had been cut off at every pass by MSH (mohan n.d.). It was indeed a miracle that Bhōjpurī survived the way it did in Trinidad. In India however, Bhōjpurī and many other vernaculars that enjoyed their day in the sun, especially in the literary world, had fallen to Khaṛī Bōlī as the authoritative standard, being granted the title of MSH due to politico-linguistic developments in the modern period. This resulted in the designation of the “Hindī Belt” that now considered vernacu- lars from Rajasthan to Bihār being vernaculars of MSH. This is illustrated in Figure 2.

At the time, Indian immigrants came to Trinidad under the contract of indentureship, such an understanding of MSH and so called vernaculars of this perceived standard did not exist. As mentioned before, most of the immigrants here in Trinidad and elsewhere in other colonies who came from the northern regions of Hindustān designated their language Hindustānī. At that time there seemed to be no linguistic differentiation between vernaculars and even languages. The idea of differentiation of the Hindustānī language into further subdivisions was initiated in 1898, when Sir George Grierson was appointed superintendent of the Linguistic Survey of India. In 1903, he began compiling all the data collected about the languages of India for the purpose of classifying them. Some conclusions that came out of that survey is demonstrated in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3.Classi cation of North Indian (Indo-Aryan Languages. Source Wikipedia)

Towards the end of the 19th century, Grierson noted that two distinct prose styles had evolved out of Khaṛī Bōlī (kinG 1994). These were to become MSH and MSU, languages that came to bear nationalistic pride after the Partition and independence from the British. They represented politico-religious forces within India and threatened to absorb much of the diversity of India’s rich heritage under the banner of Indian nationalism. As an outcry to preserve their unique identities, the language de nitions and classi cation that came out Grierson’s survey were utilized by the various regions of India to des- ignate their unique linguistic and hence cultural heritage. Thus, previously in the Bhōjpurī speaking area, during indentureship, the western Bihār and eastern UP residents called their language Hindustānī . Those who emigrated left behind the nal stages of the linguistic conquering of Bhōjpurī to become known as one of the vernaculars of MSH on the eastern end of the Hindī Belt. To hold on to their Bhōjpuriyā linguistic and cultural heritage they began calling their speech Bhōjpurī, a vernacular of the Bihārī dialect (a term coined by Grierson) of Hindustānī, still misunderstood today as being a dialect of MSH. A half a world away in Trinidad however, the central core of Bhōjpurī came to life as a language still referred to as Hindustānī.

As mentioned earlier, Trinidad Hindustānī is seen to be a koine derived from a heterogeneous mix of Hindustānī dialects of Bhōjpurī speaking area. Thus Bhōjpurī, being the Hindustānī variety with the “critical mass”, became the central core of Trinidad Hindustānī, and fusion of it obliterated all other Indian languages that had come to Trinidad, and all the dialects of Bhōjpurī outside this core (mohan n.d.). This language spoken on the estates in Trinidad, continued to evolve after Indentureship ended in 1917, assimilat- ing many words and grammar elements from French and English. Its evolution yielded a variety of Hindustānī unique to Trinidad called Trinidad Hindustānī (often also referred to as Trinidad Bhōjpurī).

During the time of Indentureship, and shortly after, Trinidad Bhōjpurī remained within the realm of being only a spoken language, much like the French Creole and English Creole that existed on the island. It was an ethnic language of the Trinidad Indian diaspora, however, it was not a language utilized for formal expression and documentation of Indian culture. Much of the essential written material that was necessary for the community’s knowl- edge on Indian culture came out of India. By this time MSH was the of – cial language in which such material was written. Many of the anthologies, manuscripts and documents that came out of India which served to educate the diaspora on their Indian heritage were in MSH. It is also worthy to note that, even from the time of Indentureship many of the laborers never saw Bhōjpurī as anything but a vernacular of MSH. The same politico-linguistic agenda in India that saw the Hindustānī varieties of classical literary acclaim,

such as BrajBhāṣā and Avadhī, become considered mere dialects of MSH, also had crippled Bhōjpurī in a serious way. The indentured immigrants had already had a notion that their speech of Bhōjpurī was not even a vernacular of MSH, but a broken or corrupted form of it. This notion was passed on to the descendants of these immigrants and is a major reason for it virtual extinction in the present day.

Bhōjpurī, since much before the 19th century, has always remained an oral tradition. It has never enjoyed great literary fame like other forms of Hindustānī. During the time of the Linguistic Survey of India, Bhōjpurī was classi ed as being part of the “Bihārī” group (see Figure 3). Grierson was the rst to use this term “Bihārī”. His reasoning for this designation differed from the understanding of earlier scholars who called Bhōjpurī a branch of Eastern Hindī. But this was a ground breaking idea as for the rst time the Bihārī dialects were beginning to be viewed as descended from a separate branch of the Indo-Aryan family of languages than MSH. Grierson, through his Linguistic Survey, had gathered enough evidence to show that while MSH was postulated to have descended from Śaurasenī Prākrit, the Bihārī group of speeches had evolved out of Māgadhī Prākrit, two distinct spoken vernac- ulars of Sanskrit. B. Saksena, in 1937, gives the following isoglosses in an attempt to establish the linguistic boundary between Avadhī (derived from Ardha-MāghīPrākrit) and Bhōjpuri (SakSena 1971):

“The distinguishing features of Bhōjpurī”,

1. The present tense with the enclitic “lā”

2. The past tense –l

3. The dative postposition “lā”

Figure 4 The Bihārī Languages

These features are shared in all three Bihārī speeches which are the most western of what is known as the Māgadhan branch of the Indo-Aryan family of

languages. This branch of languages has been derived from Māgadhī Prākrit. Figure 4 illustrates these three members of the Bihārī group.

Even much later, in the 20th century, U.N. Tiwari further argued that within the trio of Bhōjpurī, Magahī and Maithilī, Bhōjpurī should be considered separately from the latter two as they are closer in form and literary tradition (tiwari 1994). These new considerations of the Indo-Aryan languages of Northern India gave rise the revolution that rede ned this family tree. Figure 5 illustrates the current concepts of the Indo-Aryan group of languages.

Figure 5 Indo-Aryan Family Tree.

As clearly seen in Figure 4, MSH/MSU are not even a sister language to Bhōjpuri, but are more like cousins.

Based on the evidence presented thus far, a linguistic analysis of the eth- nic language referred to as Hindustānī in T&T gives a classi cation of the Trinidadian variant of Bhōpurī (Trinidad Bhōpurī designated by mohan). As proven by the above analysis, Bhōpurī is in fact a language distinct from, rather than a derivate of MSH. Many in T&T still refer to Bhōpurī as “Broken Hindi”. One fact that lent credence to this notion is that there is a high degree of lexical similarities between Bhōpurī and MSH in contrast with grammatical difference between them (mohan 1978).

Because they come from sister Prākrits (spoken varieties of Sanskrit) they share a great deal of vocabulary, however, they differ in in ection and con- jugation. Phonetics is also another aspect in which they differ. The following are some examples of how these two languages differ:

Phonetics

Vowels

1. The closed vowel “a” in MSH is pronounced as “a” in the English “what’; in Bhōjpurī it is more rounded and sounds like the “o” in the English “owl”.

- Short vowels are seldom found at the end of a word in MSH but are often found in Bhōjpurī.

- In MSH diphthongs are pronounced smoothly, however they tend to be split into two separate vowels in Bhōjpurī.

- There is a tendency to nasalize more in Bhōjpurī than MSH.

- Short vowels in MSH are sometimes lengthened in Bhōjpurī.

- Long vowels in MSH are sometimes shortened in Bhōjpurī.

Consonants

- The sounds “ś” and “ṣ” in MSH are pronounced as “s” in Bhōjpurī.

- “y” in MSH is pronounced as “j” in Bhōjpurī.

- “l” in MSH is pronounced as “r” in Bhōjpurī.

- “v” or “w” in MSH is pronounced as “b” in Bhōjpurī.

- The guttural consonants that occur in MSH from Perso-Arabic loan words are not existent in Bhōjpurī.

- “z” in MSH, a Perso-Arabic sound, is pronounced as “j” in Bhōjpurī.

- Compound consonants in MSH are pronounced as two separate conso-nants in Bhōjpurī.

- The consonant “ksha” in MSH becomes an aspirated “ch” in Bhōjpurī.

Vocabulary

There are shared words in both MSH and Bhōjpurī that are commonly used in the daily speech of both languages:

There are some words that both MSH and Bhōjpurī share, but they occur at different frequencies in both languages:

There are words that are unique to each language that come from their respective Prākrit predecessor:

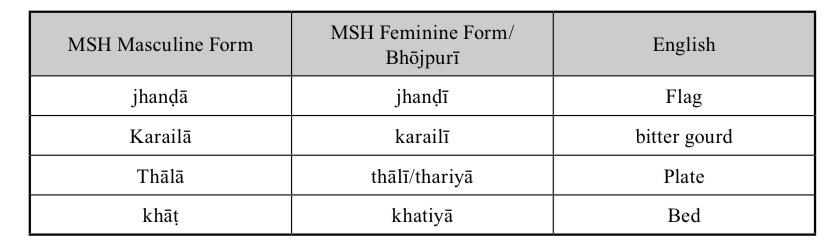

In MSH there may be diminutive feminine words used for objects in a miniature form as opposed to the masculine form denoting the same object but in a larger form. The diminutive feminine form is used in Bhōjpurī for both large and small forms:

Grammar

Nouns

1. In MSH all nouns have a grammatical gender that dictate gender agree- ment, however, in Bhōjpurī gender of nouns may be limited to animate object, especially people. In Bhōjpurī grammatical gender agreements are nonexistent.

2. In MSH the concept of de nite and inde nite articles do not exist and it is inferred in context. However, suf xation achieves this in Bhōjpurī. Adding the suf x –wā and

–iyā creates de niteness for the noun:

MSH: ghōṛā (a horse or the horse)

sēj (a bed or the bed)

Bhōjpurī: ghōṛā (a horse); ghōṛwā (the horse) sēj (a bed); sejiyā (the bed)

These suf xes can also be used with animate objects, especially peo- ple, to give an affectionate, diminutive or pejorative sense.

Tenses in MSH and Bhōjpurī have different systems of conjugation in each language. These are the hallmark sign that they have descended from different branches of the language tree. Here we conjugate the verb “dēkh-” (to see) in both languages:

We can conclude here that the standard variety of Hindustānī in modern day India, Khaṛī Bōlī, designated MSH, is not the same that formed the Hindustānī of the diaspora, speci cally of T&T. Bhōjpurī, the Hindustānī of the diaspora, is in fact not even a vernacular of MSH, but a separate language in its own right. It comes from a rich oral tradition that highlights the day to day life, philosophy, festivals and religious practices of the Bhōjpuriyā people who formed the majority of the T&T Indian diaspora. The Mauritian Indian diaspora, who share a similar Bhōjpuriyā history to T&T, has been the exemplars in promoting language within the context of culture. We look upon Mauritius with great pride as, apart from being the advocates of promoting MSH, more than even India itself, it has gone a step further and succeeded in introducing Bhōjpurī as a language being taught at primary school level. It is a fact that in all diaspora countries, the ethnic language of the diaspora peoples is on the decline and is threatened with extinction in the face of globalization. Even India itself is no exception. MSH is only spoken among the preferred language of the uneducated lower classes in India. The upper classes who can still understand and speak Hindī, now seldom prefer to speak in English, the language that represents upward social mobility. A story that is very similar to Bhōjpurī in T&T. Despite these negative telltale signs, there may still be hope. In the Lesser Antilles of the Caribbean many of the erstwhile French

colonies have taken pride in their French Creole culture. There have been efforts to preserve the language of French Creole by creating an orthogra- phy and standardized grammar. The fruit of all these efforts is seen in the establishment of grammar books and dictionaries to teach French Creole to adult and child alike. All this is for the purpose of cultural maintenance and sustainability. This is an asset in preserving the identity of a people, a quality so essential in the psyche of an individual. The same can be done for Bhōjpurī and MSH. We have seen the beginnings of it in the work done by Sarita Boodhoo in Mauritius and Motilal Marhé in Suriname. In Mauritius there are books available to learn Bhōjpurī and in Suriname there is documentation of a “Sarnami Byakaran” (Surinamese Hindustānī Grammar). Recently there is a Surinamese Hindustānī dictionary available online. In the spirit of uneSco’s rights of a child to know his identity through his ancestral/ethnic language, we must strengthen efforts to preserve whatever we can of the Hindustānī language of the Indian diaspora.

References

bahri, Hardev (1960) –“Persian In uence on Hindi.” Bharati Press Publibations. kinG, R. Christopher (1994) –“One Language, Two Scripts: The Hindi Movement in

Nineteenth Century North India.” Oxford University Press.

mohan, Peggy (1978) –“Trinidad Bhojpuri: A Morphological Study.” University of

Michigan; unpublished doctoral dissertation.

mohan, Peggy (n. d.) – “Trinidad Bhojpuri: A Brief History of Power.” Unpublished. motiLaL, Marhé (1885) –“SarnamiByakaran: EenElementaireGrammatica Van Het

Sarnami.”, Cip-GegevensKoininklijkeBibliotheek.

rai, Amrit (1984) – “A House Divided: The Origin and Development of Hindi/

Hindavi.” Oxford University Press.

SakSena, B.R. (1971) –“Evolution of Awadhi (A Branch of Hindi).” Motilal Banarsidass

Publishers.

ShackLe, Christopher & Rupert Snell (1990) –“Hindi and Urdu 1800: A Common

Reader.” Heritage Publisher.

tiwari, UdaiNarain (1994) –“The Origin and Development of Bhojpuri.” The Asiatic

Society, 1960.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindi_ Belt http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-Aryan_languages

भारत की तरह औपनिवेशिक भारतीय प्रवासी भारतीयों ने आधुनिक स्टैंड-अप हिंदी (MSH) को हिंदुस्तानी भाषा के आधिकारिक रूप के रूप में मान्यता दी है। हिंदुस्तानियों के मानक के रूप में दिल्ली की खासी बोलि को अपनाने के लिए भारत द्वारा राष्ट्र -वादी कदम को अंतर्राष्ट्रीय भारतीय प्रवासी में दिखाया गया है। त्रिनिदाद और टोबैगो (टीएंडटी) में, अंग्रेजी भाषा की भाषा होने के बावजूद और त्रिनिदाद इंग्लिश क्रेओल लिंगुआ फ्रेंका होने के बावजूद, एमएसएच को अभी भी भारतीय प्रवासी समुदाय के भीतर पढ़ाया जाता है। ये प्रयास जातीय समुदाय होने के उद्देश्य से इस समुदाय की पैतृक भाषा के किसी भी तरीके या रूप को बनाए रखने के प्रयास में हैं, जो सांस्कृतिक अभिव्यक्ति और पहचान की भूमिका को पूरा करता है। इसके बावजूद एमएसएच केवल प्रवासी भारतीयों के एक बहुत छोटे हिस्से में संचार की भूमिका निभाता है, जिसमें पोस्टकोलोनियल भारतीय आप्रवासी शामिल हैं।हालाँकि, औपनिवेशिक काल 1845-1917 के दौरान अप्रवासी भारतीय प्रवासियों के साथ आई भाषा और संस्कृति भारत में ऐसे समय से आई जब एक अलग दर्शन और भाषाई स्थिति बनी हुई थी। जिस भाषा में उनकी अभिव्यक्ति और दार्शनिक समझ शामिल थी, वह एमएसएच की तुलना में एक अलग साहित्यिक युग से आई थी। इस प्रकार, अपनी पहचान की तलाश में प्रवासी भारतीयों के सामने एक समस्या प्रस्तुत की जाती है, जब वे जवाब के लिए वर्तमान भारत की ओर देखते हैं।

यदि हम त्रिनिदाद हिंदुस्तानी को अंतरराष्ट्रीय औपनिवेशिक भारतीय प्रवासी भारतीय समाज की हठ-धूलि के रूप में परखते हैं, तो यह स्पष्ट हो जाता है कि यह भाषा, एमएसएच से पूरी तरह से अलग साहित्यिक युग से संबंधित होने के अलावा, यह एक अलग हो सकती है। एमएसएच से भाषा पूरी तरह से। यह पेपर विश्लेषणात्मक रूप से विभिन्न रूपों की जाँच करता है त्रिनिडाड हिन-डस्टानी, उदा। कहानी, भाषण बातचीत, कहावतें, और गाने। ऐसा करने के लिए, भाषा की ख़ासियत को इस बात की सराहना के लिए उजागर किया जाता है कि यह कैसे टीएंडटी के औपनिवेशिक भारतीय प्रवासी की अनूठी संस्कृति के लिए सबसे उपयुक्त है। वास्तव में, MSH ने इस भाषा के विकल्प के रूप में काम किया है, त्रिनिदाद हिंदुस्तानी के विपरीत, यह अच्छी तरह से अध्ययन, दस्तावेज और प्रकाशित सामग्री है, जिसमें से कोई भी इसे सीख सकता है। हालाँकि, यह एक भारतीय राष्ट्रवादी परिप्रेक्ष्य से आता है जो अप्रत्यक्ष भारतीयों द्वारा लाई गई अनूठी उत्तर प्रदेश / बिहार संस्कृति से अलग है। यह आशा की गयी थी

यह शोध प्रवासी भारतीयों के हिन्दुस्तानी के बारे में एक नया दृष्टिकोण लाएगा और औपनिवेशिक भारतीय प्रवासी की अद्वितीय सांस्कृतिक पहचान के प्रसार के उद्देश्य से इस भाषा के अभिव्यक्ति के विभिन्न रूपों के प्रलेखन की आवश्यकता पर जोर देगा।

मुख्य शब्द: कैरेबियाई हिंदुस्तानी, हिंदुस्तानी, हिंदी, त्रिनिदाद भोजपुरी, त्रिनिदाद हिंदी, त्रिनिदाद, हिंदुस्तानी, भाषा, संस्कृति, प्रवासी हिंदी, चटनी संगीत।

बायोडाटा

________________________________

Une grande partie de la diaspora indienne de l’époque coloniale, ainsi que l’Inde, एक reconnu l’hindi standard moderne (MSH) comme modèle प्रामाणिकता la langue hindoustani। Cette déaches de l’Inde d’adopter le Khari Boli, langue ver- naculaire de Delhi, comme le standard de l’hindoustani semble se re éter dans la diaspora indienne internationale। À त्रिनिदाद एट टोबैगो (टीएंडटी), मैग्रेल क्यू लैंग्लाइस सोइट ला लांग्यू ऑफ साइलेल एट क्यू ले ले क्रेओल डे बेस एंजेलिस डे ट्रिनिडाड सोइट ला «लिंगुआ फ्रेंका», ले एमएसएच एस्ट तौजेरस एनसिग्ने डेन्स ला कम्युनिस्टा डी ला डायस्पोरा इंडियेन। निर्भर, ला लैंग्यू एट ला कल्चर क्यूई आगमन एवेसी लेस ट्रावेल्लेयर्स एंगेजस इंडियन्स पेंडेंट ला पेरियोडे कोलोनियल 1845-1917 वेन्यू डिनेक ओने ओके फिलो- सोफी एट यूनि परिस्थिति भाषाविद् डिफेरेन्ट्स प्राइवैलेंट एन इंडेइंड एन। Par conséquent, un problème se pose à la diaspora en recherche d’identité lorsqu’le se se tourne vers l’Inde actuelle डालना obtenir des répones।

CE दस्तावेज़ का विश्लेषण लेस डिफरेन्टेस d’expression de l’hindoustani de Trinidad et met en lumière les specialités de la langue a n de montrer com- मेंटल ईल्स s sadadent au mieux à la कल्चर यूनिक डे ला डायस्पोरा indienne de T & T से मिलता है। बिएन श्री, ले MSH a servi de remplaçant कार, गर्भनिरोधक à l’hindoustani de Tri- nidad, il est bien étudié, documenté et de nombreuses publications प्रकाशन अनुमति de l’apprendre। टाउटफॉइस, il कॉन देस कॉन्सेप्ट नेशनेल इंडेन क्वीन इस्ट डिफेंटे डे ला कल्चर प्रॉपेर ए ल’युटार प्रदेश / बिहार अपॉर्टी पैर लेस ट्रैवेल्लुरस एनगेज इंडियंस Nous espérons que cette recherche suscitera une approche renou- velée de l’hindoustani de la diaspora et soulignera le besoin de प्रलेखन sur les différentes formn -expression de cette langue, a d’assurer la diffusion de cette आइडेंटिटी कल्चरल यूनीक डिक्लेयर डिले de l’époque औपनिवेशिक।

Mots-clés: hindoustani caribéen, hindoustani, hindi, bhojpuri trinidadien, hindi trinidadien, hindoustani, langue, culture, hindi d’outremer, muscul chutney हिन्द और हिन्दुस्तानी भारत को एक उपनिवेश मानते हैं, न केवल औपनिवेशिक भारतीय प्रवासी को, बल्कि वर्तमान भारत के राष्ट्र को भी। 13 वीं -14 वीं शताब्दी ईस्वी के प्रसिद्ध सू फकीर और कवि अमीर खुसरो के समय में, विशेषण हिंदी, या अधिक बार हिंदवी (हिंदू) का उपयोग किया जाता था। यह फारसी संज्ञा “हिंद” से लिया गया था, जो कि सिंध शब्द का सिंधी शब्द है, जो इंद्र नदी के लिए संस्कृत नाम है। भारतीय उपमहाद्वीप की इस्लामी विजय के बाद, विशेषण हिंदवी का उपयोग मुगल अभिजात वर्ग द्वारा सिंधु नदी (अमृत 1984) से परे भूमि में अपने नए साम्राज्य के लोगों, संस्कृति और भाषा का वर्णन करने के लिए किया गया था। स्वाभाविक रूप से, मुगल साम्राज्य के समय में, हिंदवंशियों की भाषा, हिंदावी, मुस्लिम शासक वर्ग के भारी अरबी फारसी के साथ सीधे संपर्क में थी, और uence में पारस्परिकता अप्रतिस्पर्धी थी (बहरी 1960)। इस बातचीत में से, एक भाषा को रूपांतरित किया गया था, जिसे हिंदुस्तान के पश्चिमवर्ती विजय के दशकों के दौरान अंग्रेजों द्वारा हिंदुस्तानी के रूप में संदर्भित किया गया था। वास्तव में, शब्द “हिंदुस्तानी” एक और विशेषण था, इस बार अंग्रेजों द्वारा किसी भी चीज के लिए, या हिंदुस्तान (हिंद का स्थान) से एक पदनाम। यह भाषा जो 18 वीं -19 वीं शताब्दी ईस्वी के दौरान उत्तर भारतीय उपमहाद्वीप पर लिंगुआ फ़्रैंका के रूप में अंग्रेजों द्वारा सामना की गई थी, समाज के विभिन्न क्षेत्रों में विभिन्न पदनाम थे। मुगल दरबार में इसे रेक्सटा (मिश्रित भाषा) कहा जाता था, सेना में इसे उरद-ए-ज़बान (शिविर की भाषा) कहा जाता था, और होई पोलोई के बीच इसे हिंदुस्तान के नाम से जाना जाता था, हिंदुस्तान के लोगों की भाषा कलकत्ता से दिल्ली तक हिंदुस्तान की पश्चिमवर्ती ब्रिटिश विजय की अवधि के दौरान, दासता को समाप्त कर दिया गया था। इससे दुनिया भर में कई यूरोपीय उपनिवेशों के कृषि सम्पदा पर सस्ते श्रम का नुकसान हुआ। जैसे-जैसे अंग्रेज धीरे-धीरे हिंदुस्तान पर नियंत्रण हासिल कर रहे थे, उन्होंने धीरे-धीरे नई कॉलोनी का विस्तार करते हुए मानव संसाधन पर भी नियंत्रण हासिल कर लिया। भारतीयों के श्रम के एक सस्ते स्रोत के रूप में उपयोग एक बहुत ही सरल विचार था कि अफ्रीकी गुलामों की स्वतंत्रता द्वारा सम्पदा पर छोड़े गए शून्य को रद्द करना। 1833-1920 की अवधि के दौरान, लगभग 3.5 मिलियन भारतीयों ने दुनिया भर में यूरोपीय उपनिवेशों में कृषि सम्पदाओं पर काम करने के लिए इंडेंट्रीशिप की एक अनुबंध प्रणाली के तहत हिंदुस्तान से पलायन किया। आप्रवासन के स्थानों में मॉरीशस, फिजी, दक्षिण अफ्रीका, सूरीनाम, गुयाना और कैरेबियन शामिल थे। दक्षिण एशियाई उपमहाद्वीप के भारतीय प्रवासियों के इस पलायन ने एक लचीली प्राचीन संस्कृति और इसकी गतिशील भाषा के प्रत्यारोपण को देखा, जो इन तत्कालीन कालोनियों पर आज भी स्थायी है।

भर्ती का पैटर्न जो अंग्रेजों के पश्चिमी कदम से प्रेरित था, बल्कि दिलचस्प था। यह पैटर्न इंडेंटेड मजदूरों और उनके वंशजों द्वारा बोले गए गान में स्पष्ट था। सभी उपनिवेशों में, अधिकांश मजदूरों ने उस भाषा का उल्लेख किया जिसे उन्होंने हिंदुस्तानी कहा था। हालांकि, पारस्परिक रूप से समझदार होने के बावजूद, प्रत्येक संपत्ति पर विकसित होने वाले वृक्षारोपण हिंदुस्तानी की विविधता कुछ हद तक अलग थी। प्रत्येक उपनिवेश पर अद्वितीय परिस्थितियों से वंचित होने के अलावा, यह भी काफी हद तक इस तथ्य के कारण था कि, इससे पहले, अप्रत्यक्ष अवधि में, अंग्रेज केवल दक्षिण और पश्चिम बिहार से भर्ती होने तक सीमित थे। बाद में, जैसा कि साम्राज्य पश्चिम की ओर विस्तृत हुआ, पूर्वी और मध्य संयुक्त प्रांत (आधुनिक उत्तर प्रदेश या यू.पी.) से भी भर्तियां शुरू की गईं। इसलिए, हिन्दुस्तानियों ने सम्पदाओं पर बोला, वृक्षारोपण हिन्दुस्तानी, उन जगहों पर जहाँ मजदूरों को पहले इंडेंट्रीशिप के दौरान लाया गया था, जैसे कि मॉरीशस, गुयाना, और त्रिनिदाद में, एक भारी बिह्रि अवोर था। जिन उपनिवेशों में मजदूरों को बाद में मिला, जैसे सूरीनाम और फिजी में, यू.पी. का वृक्षारोपण हिंदुस्तान था। अंदाज। त्रिनिदाद में ईस्ट इंडियन इंडेंटशिप 1845 से 1917 तक रहा। उस अवधि के दौरान, 147,592 भारतीय अप्रवासी त्रिनिदाद के तटों पर लाए गए थे। हिंदुस्तान की तत्कालीन ब्रिटिश राजधानी कलकत्ता के बंदरगाह से बहुसंख्यक प्रवासी बचे थे। ह्यूग टिंकर की रिपोर्ट है कि, 1845 से 1860 तक, कई भर्तियों में छोटा नागपुर पठार के पहाड़ी कुली शामिल थे, जो औपचारिक रूप से बिहार राज्य का हिस्सा था। मद्रास (दक्षिणी 1978) के दक्षिणी भाग से बहुत कम संख्या में भर्तियाँ निकलीं। जैसे-जैसे अंग्रेज पश्चिम की ओर बढ़ा, भर्तियों को फिर गंगा के मैदानों से निकाल दिया गया। यह पश्चिमी बिहार से शुरू हुआ और फिर पूर्वी और मध्य यूपी में विस्तारित हुआ। हिन्दुस्तानी भाषा थी MSH के रूप में जाना जाने वाला शब्द वास्तव में हिंदुस्तान की बोली से और नई दिल्ली की राजधानी के आसपास से प्राप्त हुआ था, जो मुगल और ब्रिटिश साम्राज्य दोनों के सत्ता की सीट के निकटता में एक क्षेत्र था। इस क्रिया को नाज़िक को खली बली (स्थापित भाषण) के रूप में जाना जाता है। सत्ता में इसका उदय एक जटिल कहानी है। दो मानकों के विकास की अपनी धारा का तेज। एक छोर पर एमएसएच और दूसरे पर एमएसयू। गुरुत्वाकर्षण के उनके सापेक्ष केंद्र क्रमशः हिंदो समुदाय और इस्लामी समुदाय हैं। आधुनिक समय में हिंदुस्तानियों के मानक रजिस्टरों के रूप में इन दो किस्मों के उद्भव, ब्रिटिश संप्रभुता के विस्तार और “विभाजन और शासन” की उनकी शाही नीति की दिशा में भारी थे। हालांकि, इस बिंदु पर यह उल्लेख करना उल्लेखनीय है कि मध्ययुगीन काल में लिखित भाषा के रूप में खाकी बली की खेती शायद ही हुई थी। वास्तव में, खली बली में कविता 19 वीं शताब्दी की अंतिम तिमाही तक दिखाई नहीं दी। खाकी बली के उदय से पहले, हिंदियों की साहित्यिक बोलियां भक्ति संतों द्वारा अपनाई गई थीं: ब्रजभूमि (कृष्ण भक्त), अवधी (राम भक्तों के लिए गोद ली गई) और मैथिली (बिरहर के वैवैइट्स) (bah 1960)। पंद्रहवीं शताब्दी के उत्तरार्ध से साहित्यिक हिंदुस्तानियों की प्रमुख शैली ब्रज क्षेत्र से दिल्ली के दक्षिण पूर्व में ब्रज भवन की पश्चिमी विविधता थी। इनमें हिंदो पौराणिक गुरू काना के पलायन और रोमांच की कहानी है। यह 19 वीं शताब्दी के समापन के दशकों तक नहीं था जब तक कि ब्रज भवन, और पड़ोसी खली बली का अर्थ “हिंडी” शब्द के पदनाम से नहीं था, साहित्यिक मानक के रूप में इसकी खेती के प्रति रूचि आगरा की स्थानीय मुगल राजधानी को मिली थी। इस ब्रज क्षेत्र में। अधिक उत्सुकता से अवध क्षेत्र में लखनऊ की मुगल राजधानी थी, राम मिथक का स्थान, जिसने पूर्वी हिंदुस्तान के विभिन्न प्रकार के संरक्षण को अवधी के रूप में जाना। इस शब्दशः में 16 वीं शताब्दी के कवि तुलसीदास के रामचरितमानस को लिखा गया था, जिसे आज भी पूरे हिंद साहित्य (शकील और स्नेहलता 1990) का गौरवशाली गौरव माना जाता है। 18 वीं -20 वीं शताब्दी में पश्चिम में कलकत्ता से लेकर दिल्ली तक अंग्रेजों द्वारा भारत में भाषाई स्थिति को समझने के लिए अंग्रेजों द्वारा की गई जीत ने बहुत कुछ किया। पुरानी मुग़ल राजधानियों की ब्रजभाषा और अवधी के मानकों को 1911 से ब्रिटिश राज की नई राजधानी, दिल्ली की खाकी बोलि बोली द्वारा ध्वस्त कर दिया गया था। 1800 के दशक में कलकत्ता में अंग्रेजों द्वारा फोर्ट विलियम कॉलेज की स्थापना के बाद, ब्रिटिश ईस्ट इंडिया कंपनी के धारावाहिकों और युवा नौकरों को भारतीय भाषाओं के कुछ ज्ञान प्रदान करने के लिए था। इस समय के आसपास, गद्य रचनाएं न तो हिंडी में मौजूद हैं और न ही उरदो में। न तो किस्में किसी भी महत्व की गद्य परंपराएं थीं (kinG 1994)। इस संस्था में, यह कहा जाता है कि खली बली में लेखन की उत्पत्ति हुई थी, और इस वैदिक, हिंदि और उरदो के दो प्रकारों के विभेदों की महत्वपूर्ण अभिव्यक्ति यहाँ भी शुरू हुई (किंज 1994)। इस परिवर्तन की ओर अभियान भी प्रांतीय था, जो कि प्रांतीय रुख के अनुसार न्याय की अदालतों में फारसी के प्रतिस्थापन के कारण था। इसका मतलब यह था कि इंडेंट्रीशिप की शुरुआत से, खैबली ने आधिकारिक मानक बनने की दिशा में अपनी चढ़ाई शुरू कर दी होगी। हालाँकि, यह केवल 1920 के दशक (kinG 1994) के दौरान पूर्ण रूप से सम्मानजनकता तक पहुँच गया, इंडेंट्रीशिप समाप्त होने के कुछ वर्षों बाद। इस वजह से, खली बलीहिंदी की साहित्यिक परंपरा में प्राचीनता की कमी के कारण, 19 वीं और 20 वीं शताब्दी के एमएसएच के समर्थकों और इतिहासकारों में ब्रजभाया और अवधी की पुरानी साहित्यिक परंपराएं शामिल हैं, और अधिक दूर के “हिंदी साहित्य” की चर्चा में अन्य क्षेत्रीय मानकों। अतीत। हालाँकि, जब हाल और वर्तमान के साहित्य पर चर्चा करते हैं, तो वे बड़े पैमाने पर इन अन्य परंपराओं की अनदेखी करते हैं। इस प्रकार, “हिंदी” साहित्य की प्राचीनता का मिथक इस वास्तविकता को रेखांकित करता है कि खली बली साहित्य, अप्रत्यक्ष भारतीय अप्रवासियों द्वारा हिंदुस्तानियों की मानक किस्मों को समझने के लिए कथनों से बहुत पीछे रह गया।अब हम यह बयान कर सकते हैं कि ईस्ट इंडियन इंडेंटेड मजदूरों द्वारा बोली जाने वाली हिंदुस्तानी उस समय की थी जब हिंदुस्तान की पूर्व ब्रिटिश कॉलोनी में एक गतिशील भाषाई परिवर्तन हो रहा था। इसका अनुसरण यह होगा कि, हिंदुस्तानी शब्द की समझ, हिंदुस्तान में मजदूरों द्वारा अपने वंशजों को सौंप दी गई, जैसा कि वर्तमान भारतीय डायस्पोरा में है, जैसे कि त्रिनिदाद जैसी पूर्व कालोनियों में, हिंदुस्तान में पूर्व-भाग की भाषाई स्थिति से एक थी। । त्रिनिदाद में इंडेंट्रीशिप की अवधि के दौरान, भर्ती हुए भारतीयों ने हिंदुस्तानानी नामक भाषा की बोलियों के खंडित प्रसार पर बात की। वे बोले जाने वाले वर्नाक्यूलर के प्रसार की बेहतर समझ प्राप्त करने के लिए, और जिन लोगों ने ज्यादातर योगदान दिया और हिंदुस्तानियों को भुनाया, जो कि सम्पदा (वृक्षारोपण हिंदुस्तानी) पर विकसित किया गया था, हमें अब हिंदुस्तान के उन इलाकों में और भी करीब से देखना होगा, जहां से वे भर्ती थे। टिंकर के अनुसार, इंडेंट्रीशिप (1845-1860) के पहले भाग में वे ज्यादातर छोटा नागपुर पठार के हज़ारीबाग और च्योनागपुर से भर्ती हुए थे, जो पूर्व में बिहर के दक्षिण-पश्चिमी हिस्से थे। इन हिल कुलीज ने ज्यादातर नागपुरी (सदानी भोजपुरी) और कुछ ने एस्ट्रो-एशियाई भाषा परिवार की विभिन्न जनजातीय भाषाओं पर भी बात की। कुछ अछूत भी थे जो मद्रास से चले गए और तमिल की द्रविड़ भाषा बोली। हालाँकि, लगभग 1857 से, जैसा कि ब्रिटिशों ने पश्चिम-वार्डों में विस्तार किया, भर्तियों को पश्चिमी बिहर और पूर्वी यूपी के इलाकों में गंगा के मैदानों से निकाला गया। बिहर से, इन क्षेत्रों में शामिल थे: मुज़फ़्फ़रपुर, पौना, गाय, चंपारण, साहबद, सारन और दरभंगा। ऊपर से। इन क्षेत्रों में शामिल हैं: गोरखपुर, बस्ती, गोंडा, फ़ज़बद, जौनपुर, बनारस, gzamghar, ग़ाज़ीपुर और बलिया। इन भर्ती क्षेत्रों पर हिंदुस्तानियों के वर्चस्व के प्रसार को तालिका 1 में बेहतर तरीके से चित्रित किया गया है।

टी एंड टी में, भारतीय गिरमिटिया मजदूरों द्वारा त्रिनिदाद में लाई गई भाषाओं का कोई व्यापक लेखा नहीं है (मोहन 1978)। इस मामले में किसी भी जांच का संचालन करने के लिए दो प्रमुख कारणों के लिए बहुत अलग पंथ साबित होगा। सबसे पहले, गिरमिटिया मजदूरों द्वारा लाए गए हिंदुस्तानियों के सिंदूर की स्पष्ट तस्वीर देने के लिए भाषाओं का कोई पर्याप्त रिकॉर्ड नहीं है। दूसरी बात, जैसा कि ऊपर कहा गया है कि, दक्षिण एशियाई उपमहाद्वीप नाटकीय भाषाई परिवर्तन के दौर से गुजर रहा था, उस समय के दौरान लगभग आठ दशकों तक इंडेंटशिप चली। इस प्रकार, उस अवधि में त्रिनिदाद में लाई गई हिंदुस्तानी की भाषाएं, भाषा के विकास और विकास के विभिन्न चरणों में रही होंगी। डेटा इस तथ्य को स्पष्ट रूप से इंगित करता है कि त्रिनिदाद के अधिकांश भारतीय आप्रवासी भोजपुरी की विभिन्न बोलियों के मूल वक्ता थे। यह नहीं है

एक आश्चर्यजनक तथ्य, क्योंकि अधिकांश भारतीय जहां से भर्ती हुए थे, वह उत्तर पूर्व भारत का भोजपुरी भाषी क्षेत्र था: बिहर का पश्चिमी भाग, उ.प्र। का पूर्वी भाग। और दक्षिणी या चंगनापुर का रांची पठार। यह भाषाई क्षेत्र चित्र 1 में प्रदर्शित है।

चित्र 1. भोजपुरी की उत्पत्ति और विकास से (तिवारी 1994)।

त्रिनिदाद में लाया गया भोजपुरी विशेष रूप से समरूप नहीं था, क्योंकि भोजपुरी भाषी क्षेत्र के कई अलग-अलग हिस्सों से मजदूरों की भर्ती की गई थी। उपमहाद्वीप से लाया गया भोजपुरी किसान बोलियों का एक परमाणु फैलाव था। त्रिनिदाद में ले जाए गए भारतीय गिरमिटिया मजदूरों के बीच भोजपुरी बोलने वालों का पूर्वानुभव स्पष्ट है, न कि केवल उन क्षेत्रों की एक परीक्षा से जहां से भर्तियों को उत्प्रवास के लिए निकाला गया था, लेकिन विभिन्न प्रकार के हिंदुस्तानियों के बीच हड़ताली समानताएं भी त्रिनिडाड में बोली जाती हैं और भारत में बोली जाने वाली भोजपुरी की विभिन्न किस्में। हालाँकि, जैसा कि तालिका 1 से देखा जा सकता है, भोजपुरी केवल एक इंडिक भाषा नहीं थी

इस अवधि के दौरान त्रिनिदाद। यूपी के क्षेत्रों से कुछ भर्तियां हुईं। और बिहर जो सीधे भोजपुरी भाषी क्षेत्र के लिए सन्निहित थे, जिसके परिणामस्वरूप अवधी, मगही और मैथिली बोलने वाले छोटे समूह थे। इस बात के भी पुख्ता सबूत हैं कि ये भाषाएं कभी त्रिनिदाद में बोली जाती थीं, साथ ही आगे एक बड़ी भाषाओं जैसे बंगाली, नेपाली और तेलुगु में भी बोली जाती थीं। इसी प्रकार, मद्रास के अप्रवासी दक्षिण भारत की तमिल अन्य द्रविड़ भाषाओं के साथ लाए (मोहन 1978)। तथ्य यह है कि भोजपुरी हिंदुस्तान से त्रिनिदाद में लाई गई क्षेत्रीय वर्नाकुलरों का सबसे बड़ा समूह था, इसका मतलब था कि यह “महत्वपूर्ण जन” था जो इसे लिंक भाषा (mohan n.d.) के रूप में एक उचित विकल्प बना सकता था। इसका प्रभुत्व भोजपुरी की इन विभिन्न ग्राम बोलियों में हुआ, जो भोजपुरी क्षेत्र (मोतीलाल 1885) के बाहर अन्य क्षेत्रों के मजदूरों के छोटे समूहों द्वारा लाए गए हिंदुस्तान के अन्य स्थानीय लोगों के क्रमिक गायब होने के साथ त्रिनिदादियन भारतीय प्रवासी के लिंगुआ फ्रेंका के रूप में स्फीत हो रही थीं। तमिल एकमात्र भारतीय भाषा थी जो तमिलनाडु में अछूत समुदाय से भर्ती की गई सिग्नी कैंट संख्या के कारण कुछ हद तक बची रही (mohan n.d.)। लेकिन इस छोटे से समुदाय ने भी भोजपुरी को बाकी प्रवासी भारतीयों के साथ संचार की आवश्यकता के रूप में आत्मसात किया। एक नया समुदाय अब अस्तित्व में आया था, जो भोजपुरी के आसपास केंद्रित था जो समुदाय को जोड़ता और पहचानता था। भोजपुरी, इस प्रकार त्रिवर्षीय वृक्षारोपण हिंदुस्तान की नींव थी।

भोजपुरी, वास्तव में, त्रिनिदाद और दुनिया में कहीं और नए जीवन को इंडेंटशिप के माध्यम से मिला। जैसा कि हमने देखा कि कुछ समय पहले खली बली ने मानक हिंदुस्तान बनने की दिशा में अपना काम शुरू किया था। उस समय के आसपास, भोजपुरी गुरुत्वाकर्षण के केंद्र के साथ एक भाषा नहीं थी।

चित्र 2. हिंदी पट्टी या क्षेत्र जहाँ व्यापक अर्थों में हिंदी की किस्में बोली जाती हैं स्रोत: हिंदी बीलेट; विकिपीडिया।

साहित्यिक अभिव्यक्ति और राजनीतिक शक्ति, अब तक, दोनों खलीबली में, रास्ट संकेत है कि यह वाचाल एमएसएच था। जब तक अभद्रता शुरू हुई, तब तक भोजपुरी पहले ही एमएसएच द्वारा “उपनिवेशित” हो चुकी थी, इसने विनम्र और पुरुषवादी प्रस्तुत किया। यह एक ऐसी भाषा थी जो विकसित होने में असमर्थ थी, क्योंकि यह MSH (mohan n.d) द्वारा हर पास पर काट दी गई थी। यह वास्तव में एक चमत्कार था कि भोजपुरी त्रिनिदाद में जिस तरह से बची थी। हालांकि, भारत में, भोजपुरी और कई अन्य भाषाएं, जो सूर्य में अपने दिन का आनंद लेती थीं, विशेष रूप से साहित्यिक दुनिया में, खाकी बली में आधिकारिक मानक के रूप में गिरी थीं, जिन्हें आधुनिक काल में राजनीतिक-भाषाई विकास के कारण एमएसएच का खिताब दिया गया था। इसके परिणामस्वरूप “हिंडी बेल्ट” का नामकरण किया गया, जिसे अब राजस्थान से बिरहर तक एमएसएन का वर्नाक्यूलर माना जाता है। यह चित्र 2 में समझाया गया है।

उस समय, भारतीय प्रवासियों ने इंडेंट्रीशिप के अनुबंध के तहत त्रिनिदाद में आए, एमएसएच की इतनी समझ और इस कथित मानक के तथाकथित वर्नाक्यूलर मौजूद नहीं थे। जैसा कि पहले उल्लेख किया गया है, हिंदुस्तान के उत्तरी क्षेत्रों से आने वाले अन्य उपनिवेशों में त्रिनिदाद और अन्य जगहों के अधिकांश आप्रवासियों ने अपनी भाषा हिंदुस्तानी को नामित किया है। उस समय भाषा और यहां तक कि भाषाओं के बीच कोई भाषाई भेदभाव नहीं था। हिंदुस्तानी भाषा को आगे के उपखंडों में विभेदित करने के विचार की शुरुआत 1898 में हुई थी, जब सर जॉर्ज ग्रियर्सन को लिंग्विस्टिक सर्वे ऑफ इंडिया का अधीक्षक नियुक्त किया गया था। 1903 में, उन्होंने उन्हें वर्गीकृत करने के उद्देश्य से भारत की भाषाओं के बारे में एकत्र किए गए सभी आंकड़ों को संकलित करना शुरू किया। उस सर्वेक्षण से निकले कुछ निष्कर्षों को नीचे चित्र 3 में प्रदर्शित किया गया है।

चित्रा 3. उत्तर भारतीय (भारतीय-आर्य भाषाएँ। भारतीय स्रोत। विकिपीडिया)

19 वीं शताब्दी के अंत की ओर, ग्रियर्सन ने कहा कि दो अलग-अलग गद्य शैलियाँ खली बली (किंज 1994) से विकसित हुई थीं। ये एमएसएच और एमएसयू बनने वाली थीं, जो भाषाएँ अंग्रेजों से विभाजन और आजादी के बाद राष्ट्रवादी गौरव को प्राप्त करने के लिए थीं। उन्होंने भारत के भीतर राजनीतिक-धार्मिक ताकतों का प्रतिनिधित्व किया और भारतीय राष्ट्रवाद के बैनर तले भारत की समृद्ध विरासत की विविधता को अवशोषित करने की धमकी दी। अपनी विशिष्ट पहचान को संरक्षित करने के लिए, भारत के विभिन्न क्षेत्रों द्वारा ग्रियर्सन के सर्वेक्षण का उपयोग करने वाले लैंग्वेज डे नेक्सेस और क्लासी उद्धरण का उपयोग उनकी अद्वितीय भाषाई और इसलिए सांस्कृतिक विरासत को अनदेखा करने के लिए किया गया था। इस प्रकार, पहले भोजपुरी भाषी क्षेत्र में, अभद्रता के दौरान, पश्चिमी बिहर और पूर्वी यूपी के निवासी अपनी भाषा को हिंदुस्तानी कहते थे। जिन लोगों ने उत्प्रवास किया, वे भोजपुरी की भाषाई विजय के नाल चरणों से पीछे हट गए, जिन्हें हिंदि बेल्ट के पूर्वी छोर पर एमएसएच के वर्नाक्यूलर के रूप में जाना जाता है। अपनी भोजपुरिया भाषाई और सांस्कृतिक विरासत को धारण करने के लिए, वे अपने भाषण को भोजपुरी कहने लगे, हिंदुस्तान की बिह्रि बोली (ग्रियर्सन द्वारा गढ़ा गया एक शब्द) की एक अलौकिक, आज भी एमएसएच की एक बोली के रूप में गलत समझा जाता है। हालांकि त्रिनिदाद में एक आधा विश्व दूर, भोजपुरी का केंद्रीय मूल एक ऐसी भाषा के रूप में सामने आया, जिसे आज भी हिंदुस्तानी कहा जाता है।

जैसा कि पहले उल्लेख किया गया है, त्रिनिदाद हिंदुस्तानी को भोजपुरी भाषी क्षेत्र की हिंदुस्तानी बोलियों के विषम मिश्रण से प्राप्त एक कोइन के रूप में देखा जाता है। इस प्रकार, भोजपुरी, “क्रिटिकल मास” के साथ हिंदुस्तानी किस्म होने के नाते, त्रिनिदाद हिंदुस्तानी का केंद्रीय मूल बन गया, और इसके संलयन ने अन्य सभी भारतीय भाषाओं को तिरस्कृत कर दिया, जो त्रिनिदाद में आई थीं, और इस कोर (मोहन एन डी) के बाहर भोजपुरी की सभी बोलियाँ। । त्रिनिदाद में सम्पदा पर बोली जाने वाली यह भाषा, 1917 में इंडेंट्रीशिप समाप्त होने के बाद भी विकसित होती रही, आत्मसात- फ्रेंच और अंग्रेजी से कई शब्द और व्याकरण के तत्व। इसके विकास ने कई हिंदुस्तानियों को त्रिनिदाद को अद्वितीय त्रिनिदाद हिंदुस्तानी कहा (जिसे त्रिनिदाद भोजपुरी के रूप में भी जाना जाता है) कहा जाता है।

Indentureship के समय के दौरान, और कुछ ही समय बाद, त्रिनिदाद भोजपुरी केवल एक बोली जाने वाली भाषा के दायरे में बनी रही, बहुत कुछ फ्रेंच क्रियोल और अंग्रेजी क्रियोल की तरह जो द्वीप पर मौजूद था। यह त्रिनिदाद भारतीय प्रवासी की एक जातीय भाषा थी, हालांकि, यह भारतीय संस्कृति की औपचारिक अभिव्यक्ति और प्रलेखन के लिए उपयोग की जाने वाली भाषा नहीं थी। बहुत सी आवश्यक लिखित सामग्री जो भारतीय संस्कृति पर समुदाय की जानकारी के लिए आवश्यक थी, भारत से बाहर आ गई। इस समय तक MSH – cial भाषा थी जिसमें ऐसी सामग्री लिखी गई थी। भारत से आए कई मानवशास्त्र, पांडुलिपियां और दस्तावेज जो प्रवासी भारतीयों को अपनी भारतीय विरासत को शिक्षित करने के लिए काम करते थे, वे एमएसएच में थे। यह भी ध्यान देने योग्य है कि, इंडेंट्रीशिप के समय से भी, कई मजदूरों ने कभी भी भोजपुरी को एमएसएच के एक अलौकिक के रूप में नहीं देखा। भारत में वही राजनीतिक-भाषाई एजेंडा जिसने हिंदुस्तानी किस्मों को शास्त्रीय साहित्यिक प्रशंसा के रूप में देखा,

जैसे ब्रजभूमि और अवधी, एमएसएच की मात्र बोलियाँ बन जाती हैं, भोजपुरी को गंभीर रूप से अपंग बना दिया था। गिरमिटिया आप्रवासियों में पहले से ही यह धारणा थी कि भोजपुरी का उनका भाषण एमएसएच का एक शब्द भी नहीं था, लेकिन इसका एक टूटा या दूषित रूप था। यह धारणा इन प्रवासियों के वंशजों के लिए पारित की गई थी और वर्तमान समय में इसके आभासी विलुप्त होने का एक प्रमुख कारण है।

भोजपुरी, 19 वीं शताब्दी से पहले, हमेशा एक मौखिक परंपरा रही है। इसने हिंदुस्तान के अन्य रूपों की तरह महान साहित्यिक प्रसिद्धि का आनंद नहीं लिया है। लिंग्विस्टिक सर्वे ऑफ़ इंडिया के समय में, भोजपुरी “बिहरि” समूह (चित्र 3 देखें) का हिस्सा होने के रूप में उत्तम दर्जे का था। ग्रियर्सन “बिहरि” शब्द का इस्तेमाल करने वाले थे। इस पद के लिए उनका तर्क पहले के विद्वानों की समझ से अलग था, जिन्होंने भोजपुरी को पूर्वी हिंदी की एक शाखा कहा था। लेकिन यह एक जमीनी तोड़ने वाला विचार था क्योंकि उस समय तक जब बिह्रि बोलियों को एमएसएच की तुलना में भाषाओं के इंडो-आर्यन परिवार की एक अलग शाखा से उतारा जाने लगा था। ग्रियर्सन, अपने भाषाई सर्वेक्षण के माध्यम से, यह दिखाने के लिए पर्याप्त सबूत जुटा चुके थे कि एमएसएच को अराउस्सेनी प्राकृत से उतारा गया था, जबकि भाषणों का बिहाइरी समूह मागधी प्राकृत से निकला था, जो संस्कृत के दो अलग-अलग शब्द हैं। बी। सक्सेना, 1937 में, अवधी के बीच भाषाई सीमा स्थापित करने के प्रयास में निम्नलिखित आइसोग्लॉस देते हैं (अर्ध-महाप्राक्रिति से व्युत्पन्न) और भोजपुरी (साक्षी 1971):

“भोजपुरी की विशिष्ट विशेषताएं”,

1. वर्तमान शब्द “lā” के साथ वर्तमान काल

2. भूत काल-एल

3. डिएक्टिव पोस्टपोजिशन “ला”

चित्र 4 बिहाइरी भाषाएँ

इन विशेषताओं को तीनों बिहारी भाषणों में साझा किया जाता है जो कि भारतीय-आर्य परिवार की मगध शाखा के रूप में जाने जाने वाले सबसे पश्चिमी हैं

भाषाओं। भाषाओं की यह शाखा मगधी प्राकृत से ली गई है। चित्र 4 बिह्रि समूह के इन तीन सदस्यों को दर्शाता है।

बहुत बाद में, 20 वीं शताब्दी में, यू.एन. तिवारी ने आगे तर्क दिया कि भोजपुरी, मगही और मैथिली की तिकड़ी के भीतर, भोजपुरी को बाद के दो से अलग माना जाना चाहिए क्योंकि वे रूप और साहित्यिक परंपरा (तिवारी 1994) के करीब हैं। उत्तरी भारत की भारतीय-आर्य भाषाओं के इन नए विचारों ने क्रांति को जन्म दिया जिसने इस परिवार के पेड़ को लाल कर दिया। चित्र 5 भाषाओं के इंडो-आर्यन समूह की वर्तमान अवधारणाओं को दर्शाता है।

चित्र 5 इंडो-आर्यन फैमिली ट्री।

जैसा कि चित्र 4 में स्पष्ट रूप से देखा गया है, MSH / MSU भी भोजपुरी के लिए एक बहन भाषा नहीं है, लेकिन चचेरे भाई की तरह हैं।

इस प्रकार अब तक प्रस्तुत किए गए साक्ष्यों के आधार पर, T & T में हिंदुस्तानी के रूप में संदर्भित नीति-निक भाषा का भाषाई विश्लेषण भुपुरी के त्रिनिडाडियन संस्करण (मोहन द्वारा नामित त्रिनिदाद भोरपुरी) का एक वर्गीय उद्धरण देता है। जैसा कि उपर्युक्त विश्लेषण से सिद्ध होता है, भूपुरी वास्तव में एमएसएच की व्युत्पत्ति के बजाय एक भाषा से अलग है। टीएंडटी में कई लोग अभी भी भूरी को “ब्रोकन हिंदी” कहते हैं। एक तथ्य यह है कि इस धारणा को उधार दिया गया है कि उनके बीच व्याकरणिक अंतर के विपरीत भूपुरी और एमएसएच के बीच उच्च स्तर की शाब्दिक समानताएं हैं (मोहन 1978)।

क्योंकि वे बहन प्रकृत (संस्कृत की बोली जाने वाली किस्में) से आते हैं, वे शब्दावली का एक बड़ा हिस्सा साझा करते हैं, हालांकि, वे ईशन और कॉन-जुगेशन में भिन्न होते हैं। फोनेटिक्स भी एक और पहलू है जिसमें वे भिन्न होते हैं। निम्नलिखित कुछ उदाहरण हैं कि ये दोनों भाषाएँ कैसे भिन्न हैं:

Ics फोनेटिक्स

स्वर वर्ण

1. MSH में बंद स्वर “a” को अंग्रेजी में “क्या” के रूप में उच्चारण किया जाता है; भोजपुरी में यह अधिक गोल है और अंग्रेजी में “ओ” की तरह लगता है।

लघु स्वर शायद ही कभी एमएसएच में एक शब्द के अंत में पाए जाते हैं, लेकिन अक्सर भोजपुरी में पाए जाते हैं।

एमएसएच डिप्थॉन्ग में सुचारू रूप से उच्चारण किया जाता है, हालांकि वे भोजपुरी में दो अलग-अलग स्वरों में विभाजित होते हैं।

एमएसएच की तुलना में भोजपुरी में अधिक से अधिक नाक रखने की प्रवृत्ति है।

एमएसएच में छोटे स्वर कभी-कभी भोजपुरी में लंबे होते हैं।

एमएसएच में लंबे स्वरों को कभी-कभी भोजपुरी में छोटा किया जाता है।

व्यंजन

MSH में “H” और “ṣ” ध्वनियों का उच्चारण भोजपुरी में “s” के रूप में किया जाता है।

MSH में “y” को भोजपुरी में “j” के रूप में उच्चारित किया गया है।

एमएसएच में “एल” का उच्चारण भोजपुरी में “आर” के रूप में किया जाता है।

एमएसएच में “वी” या “डब्ल्यू” का उच्चारण भोजपुरी में “बी” के रूप में किया जाता है।

फारस-अरबी ऋण शब्दों से एमएसएच में होने वाले कण्ठवादी व्यंजन भोजपुरी में मौजूद नहीं हैं।

एमएसएच में “जेड”, एक पर्सो-अरबी ध्वनि है, जिसे भोजपुरी में “जे” के रूप में उच्चारित किया गया है।

एमएसएच में मिश्रित व्यंजन का उच्चारण भोजपुरी में दो अलग-अलग कॉन्सो-नेंट्स के रूप में किया जाता है।

एमएसएच में व्यंजन “क्ष” भोजपुरी में एक “च” बन जाता है।

Abulary शब्दावली

एमएसएच और भोजपुरी दोनों में साझा शब्द हैं जो आमतौर पर दोनों भाषाओं के दैनिक भाषण में उपयोग किए जाते हैं:

व्याकरण

संज्ञा

1. एमएसएच में सभी संज्ञाओं में एक व्याकरणिक लिंग होता है जो लिंग को निर्धारित करता है- मानसिक, हालांकि, भोजपुरी में संज्ञा के लिंग को चेतन वस्तु विशेष रूप से लोगों तक सीमित किया जा सकता है। भोजपुरी व्याकरण में लिंग संबंधी समझौते कोई नहीं हैं।

2. एमएसएच में डी नीट और इंडे नाइट लेखों की अवधारणा मौजूद नहीं है और यह संदर्भ में अनुमानित है। हालाँकि, suf xation इसे भोजपुरी में हासिल करता है। Suf x -wā और जोड़ना

-आईए संज्ञा के लिए डे नाइटीनेस बनाता है:

MSH: ghHā (एक घोड़ा या एक घोड़ा)

sēj (एक बिस्तर या बिस्तर)

भोजपुरी: ghōṛā (एक घोड़ा); gh (wā (घोड़ा) sēj (एक बिस्तर); सेजिया (बिस्तर)

इन सूफ़ x का उपयोग चेतन वस्तुओं के साथ भी किया जा सकता है, विशेष रूप से peo- ple के साथ, एक स्नेही, कम या सकारात्मक भावना देने के लिए।

एमएसएच और भोजपुरी में काल प्रत्येक भाषा में संयुग्मन की विभिन्न प्रणालियाँ हैं। ये हॉलमार्क संकेत हैं कि वे भाषा के पेड़ की विभिन्न शाखाओं से उतरे हैं। यहाँ हम दोनों भाषाओं में “dēkh-” (देखने के लिए) क्रिया को जोड़ते हैं:

हम यहां यह निष्कर्ष निकाल सकते हैं कि आधुनिक भारत में, हिंदुस्तान की मानक किस्म, खली बली, नामित MSH, वही नहीं है जो प्रवासी भारतीयों के हिंदुस्तानियों का गठन किया, टी और टी की विशिष्ट रैली। प्रवासी भारतीयों की हिंदुस्तानी, वास्तव में एमएसएच का एक शब्द नहीं है, लेकिन अपने आप में एक अलग भाषा है। यह एक समृद्ध मौखिक परंपरा से आता है जो भोजपुरिया लोगों के दिन-प्रतिदिन के जीवन, दर्शन, त्योहारों और धार्मिक प्रथाओं पर प्रकाश डालती है, जिन्होंने टी एंड टी भारतीय प्रवासी के बहुमत का गठन किया था। मॉरीशस इंडियन डायस्पोरा, जो टी एंड टी के समान भोजपुरिया इतिहास को साझा करते हैं, संस्कृति के संदर्भ में भाषा को बढ़ावा देने के लिए अनुकरणीय रहे हैं। हम मॉरीशस को बड़े गर्व के साथ देखते हैं, एमएसएच को बढ़ावा देने के पैरोकार होने के अलावा, भारत से भी ज्यादा, यह एक कदम आगे बढ़ा है और प्राथमिक विद्यालय स्तर पर भोजपुरी को एक भाषा के रूप में पेश करने में सफल रहा है। यह एक तथ्य है कि सभी प्रवासी देशों में, प्रवासी लोगों की जातीय भाषा गिरावट पर है और वैश्वीकरण के चेहरे पर विलुप्त होने का खतरा है। यहां तक कि खुद भारत भी इसका अपवाद नहीं है। MSH केवल भारत में अशिक्षित निम्न वर्गों की पसंदीदा भाषा के बीच बोली जाती है। उच्च वर्ग जो अभी भी हिंदियों को समझ और बोल सकते हैं, अब शायद ही कभी अंग्रेजी में बोलना पसंद करते हैं, वह भाषा जो ऊपर की सामाजिक गतिशीलता का प्रतिनिधित्व करती है। एक कहानी जो टी एंड टी में भोजपुरी से बहुत मिलती-जुलती है। इन नकारात्मक गप्पी संकेतों के बावजूद, अभी भी आशा हो सकती है। कैरेबियन के लेसर एंटिल्स में पूर्ववर्ती कई फ्रांसीसी

उपनिवेशों ने अपनी फ्रांसीसी क्रियोल संस्कृति पर गर्व किया है। फ्रेंच क्रियोल की भाषा को एक ऑर्थोग्रा- phy और मानकीकृत व्याकरण बनाकर संरक्षित करने का प्रयास किया गया है। इन सभी प्रयासों का फल व्याकरण की पुस्तकों और शब्दकोशों में फ्रेंच क्रियोल को वयस्क और बच्चे को समान रूप से पढ़ाने के लिए देखा जाता है। यह सब सांस्कृतिक रखरखाव और स्थिरता के उद्देश्य के लिए है। यह एक व्यक्ति की पहचान को संरक्षित करने में एक संपत्ति है, एक व्यक्ति के मानस में इतनी आवश्यक गुणवत्ता। वही भोजपुरी और एमएसएच के लिए किया जा सकता है। हमने इसकी शुरुआत मॉरीशस में सरिता बूडू और सूरीनाम में मोतीलाल मरहे द्वारा किए गए कार्यों में देखी है। मॉरीशस में भोजपुरी सीखने के लिए किताबें उपलब्ध हैं और सूरीनाम में एक “सरनामी ब्याकरन” (सूरीनामी हिन्दुस्तानी ग्रामर) के दस्तावेज़ हैं। हाल ही में एक सूरीनाम हिंदुस्तानी शब्दकोश ऑनलाइन उपलब्ध है। अपनी पैतृक / जातीय भाषा के माध्यम से अपनी पहचान जानने के लिए एक बच्चे के यूनिस्को के अधिकारों की भावना में, हमें भारतीय डायस्पोरा की हिंदुस्तानी भाषा के लिए जो कुछ भी हो सकता है, उसे संरक्षित करने के प्रयासों को मजबूत करना चाहिए।

Posted

in

by

Tags: