Peter Manuel is an ethnomusicologist at City University of New York, and an authority on the music of the Caribbean. His book East Indian Music in the West Indies: Tan Singing, Chutney, and the Making of Indo-Caribbean Culture (Temple University Press, 2000) won the Caribbean Studies Association’s Best Book Award in 2001. This book is also the basis for Afropop Worldwide’s 2008, Hip Deep program on the Indo-Caribbean. Siddhartha Mitter interviewed Peter in New York. Here’s their conversation.

Peter Manuel: My background as an ethnomusicologist was mostly in India. From about 1970, I had been visiting India and was interested in Indian classical music. I studied sitar and did various research and publications on Indian classical music and also Indian popular music. My exposure to Indo-Caribbean music would have started in 1992, which is when I started teaching at John Jay College. Right from my first semester, I encountered students in my classes who had Indian names – like Rajgopal, Chandrapati or whatever – and I thought, “Oh, this is great; people that I can relate to on the Indian aspect.” But I soon discovered that they weren’t from India, they were from Trinidad or Guyana. They didn’t speak Hindi; they seemed not to know about many aspects of Indian culture. But on the other hand were very well informed on certain other aspects of Indian culture: very into Indian popular Bollywood film music for example, they knew all the songs, they could sing along with them. Chatting with them then I discovered that they had a certain familiarity with other kinds of music that I was not familiar with at all.

They mentioned certain kinds of folk songs, like Chowtal, and what they call local classical music or tan singing, of which I had never heard. I was intrigued by all this; in some ways, it was familiar to me. I also learned that there was a fairly large population of Indo-Caribbeans here in New York City; it would be over 200,000 I believe, mostly from Guyana and Trinidad. I started to make contacts with this community and, from there, my interest continued and I was able to now do several fieldwork trips to Trinidad and Guyana and Suriname.

Siddhartha Mitter: Let’s go back in time a bit. Could you describe the kind of music that the indentured laborers brought with them to Trinidad and Guyana?

P.M.: These are people who would have been coming from 1845-1917. Of course, slavery had ended in the 1830s, so these were sugar colonies in the British Empire – or, in the case of Suriname, the Dutch. There was a need to replace the Afro-Caribbeans who had left the sugar plantations so they started bringing people from India. Most of these people came from one particular area of North India that is called the Bhojpuri region nowadays, because it is where they speak the Bhojpuri dialect of Hindi. This is the area of Eastern Uttar Pradesh and Western Bihar, sort of around the city of Benares and Patna. About 80% of the people coming to Trinidad and Guyana and Suriname are coming from this area. These are mostly illiterate peasants; they are farmers. A handful of them would be literate. This small group would be of Pandits or people who claim to be Brahmans. These people would be in demand for religious events and so on. But mostly there is a rural folk culture that these people would have brought with them. In the realm of music, it is going to be mostly traditional folk songs of that region.

Now, these would fall into various categories. One big category would be women’s songs that women sing amongst themselves at childbirths, at weddings, at other sorts of life-cycle events, work songs. Many of these songs have now disappeared, both in India and the Caribbean, but some are still alive in both areas, or they have been transmuted in different ways. Chutney is one example of this which maybe we can talk about later. Anyhow, that would be one category of songs brought. There were also traditions of drumming. For example, there were semi-professional drummers who play what they call tassa, which is a drum ensemble that you can find in North India. It is very popular in Trinidad, and is absolutely essential at Hindu weddings in Trinidad, and also at Trinidadian and Guyanese Hindu weddings up here in the New York City area. As a result, you have several of these tassa drum ensembles here; it is a very much a dynamic and living tradition here.

Then the question arises, “Did they bring any sort of classical music traditions with them?” When people think of Indian music, they think of sitar and Ravi Shankar. There would definitely not be much of that type of music. The immigrants are not sitarists from the court of Lucknow; they are farmers. These farmers would not have sitars and probably would not even have much familiarity with that type of music. They might have heard semi-professional or intermediate versions of classical music in temples, for example. As a result, there might have been an awareness of this kind of music, but definitely not a strong tradition.

Nevertheless, as these Indian communities formed – let’s focus on Trinidad and Guyana during the late 1800’s – these people are mostly either living on plantations; or performing indentured work for five or seven years, moving off the plantation, setting up some Indian villages, and becoming farmers. The Afro-Caribbeans are mostly living in the cities and towns, so there is not a whole lot of contact with them. And so these new immigrants are, in many ways, free to develop or preserve as much of their Indian culture as they wanted. New people are coming from India, refreshing the memory of different kinds of songs and so on. Communities take shape, perhaps even with semi-professional musicians. These semi-professional musicians would be singers mostly or drummers who are invited to perform at weddings or prayer sessions where they want someone to sing some sort of specialized songs instead of a simple congregational song.

As these Indo-Caribbean communities take shape and assume their own sort of direction and form – by the time we get to 1910-1920 – they have their own traditions of music. 1917 is the last year in which people came as indentured workers. After that, there was no further input from this Bhojpuri region of India. You’d have occasional holy men coming from India, you would get films and so on coming in the 1930s, and handfuls of records. In other ways, they’re very cut off from India. But by this time they’ve also established their own musical traditions, such that if someone came from India and said, “Oh no, you’re singing that song wrong; that’s not how it goes,” instead of obsequiously trying to correct themselves, by this point the Trinidadians and Guyanese might say, “Well, this is the way we sing it here, and you’re welcome to sing along with us if you want to learn our way.”

So, what I encountered then in my research right from the start was this mix of an old stratum of traditional folksongs, much of which seems to be sung in essentially the same way as it still might be sung in India today, as I can verify now because of my own fieldwork in India. Also, you find the same folksongs being sung in Fiji, another destination for indentured workers from the Bhojpuri region during the same period. So, if you find something sung in Guyana and the same thing sung the same way in Fiji then you know it came from India because Guyana and Fiji have no particular contact with each other. So, you have this one traditional stratum of old songs and old genres, including some things that may have died out or declined in India itself. Then, there are other things that have clearly changed, but along Indian lines and not necessarily through any particular Afro-Caribbean influence.

I got very interested in this genre that they call local classical music or tan singing which is their sort of reconstruction of the fragments of Indian classical music that they had heard or that a few knowledgeable people had brought. There would be a certain demand for this at weddings or at certain prayer functions where they wanted to have serious, semi-professional singers. I was intrigued by this kind of music because it was as if they had taken these fragments that they had gotten from handfuls of records or some knowledgeable people that had come a hundred years ago and put these things together in their own way, including genres that sound like North Indian classical music genres: thumri, kilana, or terana, ghazal, dhrupad, kafi, and behag (which is a raga in North India but more like a genre in the Caribbean). I was struck by these terms and I could see some similarities with North Indian dhrupad and the Caribbean dhrupad, but it was obviously very different. It was as if they had gotten some fragments, had put them together in their own way, and at a certain point it became an established style. There was a right and wrong way of singing it, a certain aesthetic to it. If they heard Ravi Shankar or some musician from India, they weren’t necessarily interested in that interpretation; they had their own way of doing it.

S.M.: It feels like it’s a conscious or semi-conscious attempt to redevelop one’s own history: to write or to create, to identify a history and to trace one’s ancestry and one’s history back amongst people who might not have had a lot of documented or archived material, right? It sounds like it’s not an invention of tradition because clearly they’re drawing on existing musical styles and traditions. Is the development of tan singing and this idea of a local classical music to some extent an act of cultural, community cultural nationalism in a way, a cultural affirmation?

P.M.: In some ways; it’s very complicated. During the formative years – let’s say the first half of the 20th century – they were getting records of film music from India from the 1930s, but this doesn’t really relate to this semi-professional tan singing or local classical music. Tan singing was a more serious type of music that would be sung at special occasions; of course, it’s serious in a way, but also very lively, rhythmic and exciting. Was it a self-conscious cultural affirmation? Well, certainly the practitioners and enthusiastic audience members would appreciate it as something traditional. This was the Indian tradition; the words are old, beautiful, and meaningful. Many people, I’ve found, are very moved by the words, even if they had only learned what they meant, and whether they were conversational in Hindi or not (generally they weren’t). But even if they didn’t know what the words meant, they knew that they came from old books and culture, and for them it was an important source of tradition. They could appreciate that even though they loved the film music records they were getting from the ’30s and ’40s. Those records were pretty and fun, but the people who liked tan singing or performed it felt that this was something more serious or rich.

Now, from my perspective, arriving on the scene in the ’90s with a pretty good knowledge of North Indian classical music, I could hear that it was very, very different. I would ask old people, “Where did this music come from?” and they would respond, “Well, it came from India.” I would say, “Okay, well, how did you learn this thumri? Because I’ve heard thumri in India, and it sounds very different.” They would say, “Well, this is how we learnt it; this is how I heard it from the old people when I was young.” No one could ever acknowledge that this music might have evolved or developed, and I think it probably happened, as I said, in the early decades of the 20th century that it somehow took this shape.

S.M.: What are a few of the crucial differences between North Indian classical music, Hindustani classical music, and tan singing?

P.M.: Well, first of all, North Indian classical music has a whole system of ragas [Indian musical modes], which they don’t really have in the Caribbean. In the Caribbean it is more a question of song genres – that is, vocal songs with lyrics taken out of old books, and some of these books are from the 19th century. These people prize them and hoard them – very zealously guarding them, in some cases.

Big differences? Well, let’s say they sing something called dhrupad. This is a serious song, and if you know anything about North Indian classical music, you’d know that dhrupad is a very traditional genre; it probably thrived mostly in the 17th and 18th centuries, but it’s still going. A dhrupad is a serious vocal song and can be done in a classical style, but dhrupad is also performed in temples in North India in a certain style – a sort of parallel tradition – and I suspect this Caribbean tradition came from that. When there is a tan singing or local classical event in the Caribbean for which someone has hired professional musicians, they would hire a team of one or two singers and a drummer who plays this dholak barrel drum and a duntow, which is this metal rod that we can talk about later. The singer will accompany himself playing harmonium, and you always start out with a dhrupad – that is, a serious song – just like in India. The text might correspond to a text that you would find in India, because maybe they’re getting it out of some book. It starts out very slowly and then there’s a section where they double the lyrics and they’re singing the lyrics twice as fast, which also has a certain parallel in North Indian dhrupad style. Aside from that, it’s pretty different. It lasts about five minutes, there’s none of this long-winded alap [introductory improvisation out of rhythm] going on for half an hour or an hour. These are short songs; the emphasis is on the song rather than the improvisation, they don’t really know anything about raga, but they have an idea of correct and incorrect ways to play dhrupad; the song should go a certain way, the drum accompaniment should go certain way, and so on.

They don’t have the same sort of knowledge of theory that you would get in Indian classical music. If you ask an Indian classical drummer, “Why did you play that rhythm on your tabla?” he’ll say, “Well, this is a tala, or a meter of fourteen beats and this is how it goes, and this is the teka section and it has this particular structure.” Or, if you ask a classical singer, “Why did you sing that note there and not another note?” he can say, “Well, I’m singing this particular raga, this mode, and this is an important note in it, and I don’t want to sing that other note because then it will sound like some other raga.” This is what we call theory: referring to abstract elements of melody and meter and so on. I tried to have these sorts of conversations with musicians in the Caribbean and they just don’t have that sort of knowledge, that sort of formal abstract theory. But, if I could play something for them – let’s say a certain sort of recording – they’ll say, “Oh this drummer, he’s playing wrong. That’s the accompaniment that should be used for thumri and he’s playing it for behag; he doesn’t know what he’s doing.”

S.M.: That puts a huge importance on transmission, on having elders and so forth that you can learn from. If it’s not being archived, if you will, or systematized in theory and so forth, then it’s transmitted through practice.

P.M.: Yes, it’s an oral tradition in that sense, which also makes it a little bit vulnerable. Something like Indian classical music can now be transmitted in so many ways; there are websites, there are books in Hindi, English, etc. You may not be able to learn the ragas and talas perfectly, but you can learn a lot of stuff. It’s reinforced in so many ways. Oral traditions are a little bit weaker that way; they are dependent on this sort of transmission. Of course, a lot of this repertoire was based on the songs and the meaning of the words, and in Trinidad and Guyana now people don’t really understand Hindi, so the appeal of it has declined and the audience has changed.

I think, to some extent, this may have actually contributed to a certain kind of enrichment or dynamism for a time. It may have been an incentive to make it musically more interesting than just a plain folksong. For example a lot of the dholak players in Trinidad and Guyana and Suriname – the dholak being a barrel drum, a two-headed drum that you put it on your lap as you sit cross-legged – are terrific. They can hold their own against the hottest Indian folk drummers as far as I’m concerned. Perhaps as the comprehension of language declined they compensated to some extent by paying more attention to musical form than would have happened in a simple folk tradition. But definitely with the decline of language and the lack of any sort of formalized pedagogical system, the popularity of the music has declined.

Also, for better or worse, there’s a certain presence of Indian classical music now in Trinidad and to some extent Guyana and up here. Someone goes to India and studies tabla or sitar or another instrument, and comes back to Trinidad and starts teaching lessons privately or in little schools. People can learn that genre, so young Trinidadians or Guyanese who are interested in music might ask, “Well, why should I learn this traditional, folksy music that our elders used to sing when I can learn to play Ravi Shankar style?” You can’t really argue with that; obviously North Indian classical music is a richer tradition. That said, from my perspective, the Guyanese and Trinidadian local classical styles are unique and they have their own kind of beauty and charm. It’s too bad that they are declining that the extant musicians who are still around don’t get the recognition that they could get if there were a real sort of revival of popularity of this music.

S.M.: Amongst Indo-Caribbeans, do different kinds of musics develop in Guyana versus Trinidad and vice versa?

P.M.: In the realm of local classical music there are some similarities and some differences, and it’s very hard to reconstruct how this happened. A few influential musicians might have changed things. Obviously people are going back and forth to some extent. In the old days it would be by boat; it must have taken a day or two to make that trip in 1910. Musicians in both places would be eager to meet musicians from the other places. But even comparing one part of Guyana – like Berbice – with another region of Guyana, people say they sing differently, different folk songs, different styles, or maybe the same genres but in slightly different style. This used to be true in Trinidad too, although Trinidad is better oriented. So you have certainly regional variations – and then you have Suriname, which is its own sort of world. In some regions, about 80% of the people came from this one area of India, the Bhojpuri region, bringing this musical tradition. I don’t want to say that they brought a unified body of songs from India, because Bhojpuri is a big region that it must have 20 or 30 million people, but when they find themselves in these new communities in the Caribbean, to some extent common musical languages of folksongs are formed and, for various reasons, musical varieties persist.

Meanwhile, some things are done the same everywhere in ways that are very curious. I mentioned before this instrument called the duntow. This is a metal percussion instrument. It is a metal rod that is about four feet long and you play it with this little u-shaped clapper. So as you’re sitting cross-legged on the ground, you have it plopped in front of you pointing up and you’re going sort of ching-chinga-ching-chinga-ching-chinga-ching. Not everyone can play it, but lots of people, whether it’s young boys or whatever, learn to accompany – this is, accompany songs of various kinds. I don’t think you’d accompany a film song with it, but certainly folksongs and bhajans [a sort of Hindu devotional song]. It’s everywhere in the Caribbean, it’s everywhere in Fiji – Fijians having come from the same part of India. The funny thing is, you go to India, and outside of the Bhojpuri region you won’t find it at all. A Surinamese colleague of mine has documented its existence in the Bhojpuri region – both the name and the instrument – but it is very, very obscure. So, this is one of the sort of enigmas of diasporas: why something can become so popular when either it died out or fizzled out in the ancestral homeland.

S.M.: So I want to ask you few things about the impact of various kinds of social and political changes in these countries and these communities over the century, but first, tell me about the Alan Lomax episode.

P.M.: As a musicologist, I’m really interested in trying to reconstruct some of the historical aspects of the music. Whether we’re talking about folk music or local classical music or whatever, what did they create themselves in the Caribbean, if we’re talking about the Caribbean, and what came from India? In some respects these issues are very important to Indians themselves. In some contexts they might pride themselves on having created something in the Caribbean. They say, “Chutney? Oh, we Trinidadians invented Chutney, or we invented the duntow;” things that might or might not be true. In some cases, they might pride themselves on singing something or preserving something that is very old.

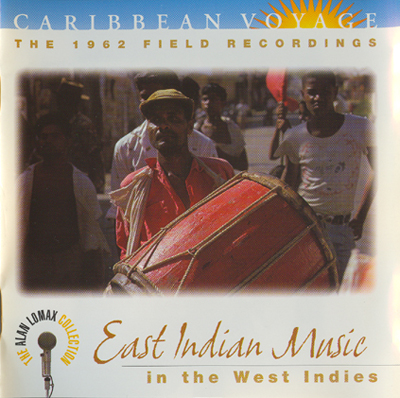

So, recordings are very important. We wish there were more of them. There were some made in the late ’30s and early ’40s in Trinidad, but they’re just sort of imitating the records of film songs and popular songs that they were getting from India at that point, so they don’t really tell us anything about Indo-Caribbean music. We don’t really have any recordings of Indo-Caribbean music, per se, until Alan Lomax, who is this energetic ethnomusicologist that some of you will be familiar with who goes around the world, especially in the early ’60s, to Africa, the Middle-East, Italy, Spain, and the Caribbean, recording everything he can and doing a terrific job at it. His recordings, whether we’re talking about of rural Spain, or some village in Italy where they’re singing in some language that no one even understands anymore, or in the Caribbean, are incredibly valuable.

He did a whole set of recordings in Trinidad, and these recordings, incidentally, are housed at an annex of Hunter University, which is over by Port Authority Bus Station. Many of them have now been re-issued in a series of Rounder Records, and I worked on the Trinidadian one. Lomax recorded a lot of Afro-Trinidadian stuff, which is a whole other subject, because those songs have disappeared – Yoruba songs and so on. He was also very open minded; he realized that Trinidad was not just calypso and steel band and Afro-Caribbean traditions, but also these Indian traditions. He did a lot of recordings there. He recorded a pretty good gamut of what could be heard at that point. Much of this is presented on a CD that I edited for Rounder, but of course Lomax himself did the recordings and took fantastic field notes and beautiful pictures – I mean, this is a very remarkable ethnographer.

So, what did he record? There would be things like, for example, women’s folksongs. There’s one on CD, “Juxaar,” which is a grinding song. So you hear this grinding wheel that the women are using going zhhhzhhhzhhhh, and I guess they’re putting chickpeas or something into it and there’s a certain song that you sing with that, which would be in Bhojpuri Hindi, and we presume that it came from India – but perhaps some of them didn’t. Perhaps some of them were made by Indians because the Indians in the Caribbean were composing their own songs, but in traditional style. “Juxaar” would be in the category of a traditional Indian women’s folksong. Even in India a lot of these work songs disappear as things get mechanized and people don’t sit around the grinding wheel anymore.

He also recorded Chowtal. This is another kind of traditional Indian folksong, but a variety that is still widely sung in Trinidad and Guyana during the what they call Phagwah or holi spring festival. This is usually in early March and the last weeks of February. It is what musicologists call an antiphonal song. In antiphonal songs, two groups sing back and forth at each other. You’d have a line of men seated on the ground, maybe six of them, and they sing one line. And then they catch their breath and the other men repeat the same line, and this is accompanied by the dholak, a barrel drum. And then they sing it a certain number of times, and then they change the rhythm. And then you proceed to the next line and it’s going faster and faster. It’s not a sort of music that you are meant to listen to; rather, it’s really all about being in this group and singing it. When it’s done well – and for that it takes a little bit of practice with the group – you go through these lines and it gets faster and faster and there are tricky rhythmic modulations; it’s great fun and people get very excited and worked up. It’s a popular thing; you have all sorts of little temple groups, Hindu temple groups, whether we’re talking about Trinidad or Guyana or Suriname or Queens, New York.

They have little competitions. During these weeks leading up to holi, you have groups that do house visits where they go and visit the house of some friend and sing for a few hours, and then the host gives them food and drink and stuff like that. People might even get up to dance; whatever social inhibitions existed in India regarding dance are things of the past in the Caribbean. Indo-Caribbeans, at the risk of generalizing, will dance at the drop of a hat, in traditional Bhojpuri style, and usually the best dancers are the old women. At any rate, Chowtal is not specifically a dance genre, but I’ve seen people dance to it when it gets fast and lively. At any rate, that’s another category of folksong that Lomax recorded, and it’s basically the same as is sung today; you can hear plenty of it in Queens, NY in February and March if you hook up with the right people.

I went to India in January of ’07, tramping around the Bhojpuri region, looking for it, expecting to find it all over the place; this was holi season, or the beginning of holi season: end of January, early February. Surprisingly, I had a hard time finding it. When I did find it, my friends that I went with from this other village, said they’d never heard anything like it. I think it exists in pockets in India; there are, after all, big and under-researched areas. So it may exist in quite a few pockets, but it was definitely not a well known genre, and it’s again a sort of a mystery. Why is it so popular in the diaspora, Guyana, Trinidad, and Fiji?

S.M.: I need to ask you, where did you finally find the Chowtal?

P.M.: Well, I went to Benares, which is this city in the heartland of the Bhojpuri region, and I sort of asked everyone in sight about it and met one or two people who had heard of it or heard it, and I said, “Well where can I hear it?” I would get answers like, “Well, if you’re there when they sing it, you’ll hear it.” So, on this trip I was there in the Benares region about two weeks, and it had been sort of my mission to find this music because I wanted to compare the styles, and I was getting pretty desperate because after a week I hadn’t found anything. Then my friend said, “Oh, let’s go out for a drive in the countryside.” We were about two hours outside of Benares – sort of in the Mirzapur district – sitting and having tea. And at this point I just was becoming a ridiculous pest. Practically everyone I struck up a conversation with, I’d say, “So, have you ever heard of Chowtal?” And they’d say, “What?” And I’d say, “Oh, never mind.” At any rate, there I was sitting next to some old man and we were chatting in Hindi. He asked me what I was doing and I said, “I’m studying folk music and I’m interested in Chowtal, have you ever heard that?” And he said, “Oh sure.” And he starts singing some Chowtal and this is like, “Ok, this is what I’m looking for.”

S.M.: That’s a big moment.

P.M.: Yes, it was exciting. I mean, I think people who live in this region and who are interested in folk music know that it exists; you can find it if you’re in the right place. So he said, “Why don’t you come back tomorrow? I’ll get some friends together to sing.” This was quite a ways from Benares, but anyhow, I went back the next evening. We are walking around this Indian town, and it was sort of a surreal experience for me. There were some women singing in a house, I could hear them singing, I could see them huddled around a lamp. They were singing this song that, if any Guyanese or Trinidadian heard it, they’d say, “Oh that’s a Chutney.” I don’t know exactly what the song was or what the occasion was, but it really felt like I was back in Trinidad. Meanwhile, a noisy wedding procession passes by. The groom is seated on a horse, surrounded by a bunch of merry-makers, and preceded by drummers playing tassa drums, which is an ensemble that is everywhere in Trinidad. You cannot have a Hindu wedding without a tassa drum ensemble. Anyhow, this was all very familiar to me.

Then I found my friend that I had been chatting with at the tea stall. He was this old guy, and he said, “Oh, let me sing a few songs for you.” He sang what he called thumri and ghazel, and they were very similar to what you would hear in Trinidad and Guyana. These very idiosyncratic styles that don’t really sound like a classical thumri and ghazel that you would hear at a concert hall in New Delhi. Then we proceeded to this little temple where, sure enough, my contact had assembled, what is probably the bhajan group that sings every week, but now we were getting into holi or Phagwah season and they would switch over to singing Chowtal. I was the honored guest, so they were happy to sing these Chowtal for me. This is about twenty – well, maybe a dozen – singers. And then various other people packed in, just listening for fun. They sang one or two that were sort of different and didn’t really correspond to the things I had heard in Trinidad and Guyana, and then they sang one or two that were basically identical – which, of course, is interesting to me, because, again, keep in mind that the contact from this part of India had stopped as of 1917. You know, they’re getting Indian films, records, holy men coming, but none of that is representing this Bhojpuri folk culture. So it’s pretty remarkable that this folksong style is kept alive, and, as I mentioned, here in Queens, in Trinidad or Guyana it’s not just some doddering, toothless old man that’s doing it; it’s young people, it’s something that’s very popular.

S.M.: So I want to go back to this hemisphere, but just one really quick question: when you met a gentleman like that old man and when you got to that village, is there a cultural memory, a historical memory there of people having left or been taken away to go to the Caribbean?

P.M.: Not much. What they seem to know of the Caribbean was through a Trinidadian cricket team that had come to India, and these people would be sort of surprised to learn that they had Indians there too. And I think I perhaps met someone or another who knew that the Trinidadian Prime Minister, who was an East Indian from that area, or rather, ancestrally, had come through, but basically there’s not much awareness of that. Which is paralleled, you might say, in Guyana and Trinidad, and also Suriname and Fiji to a large extent. They obviously know they came from India; they are proud of that. But usually they don’t know where they came from, the name of the village or anything like that, or even what caste their grandparents were.

On the one hand, they are proud to be Indian, to be inheritors of a certain ancestral tradition. On the other hand, they are not consumed by a nostalgia to go back to India. They are accustomed to their new home. They are Trinidadians, they are Guyanese, and I also experienced this attitude musically in many ways. If I’m a Trinidadian and I’m really interested in Indian classical music, I probably want to hook up with an Indian sitarist. But on the whole they have their own music system. They are interested in Indian film songs and performers – Anup Jalota, a bhajan singer, for example, is well-known. But in other ways, they have their own music styles. I’m sure it started happening in the later years of the indenture period – that, by this time, the Indians have been in the Caribbean for around fifty years. They’ve got their own way of singing, their own style, and perhaps someone would come from India, let’s say in 1915, and say, “Oh no, you’re singing that folksong wrong,” or “No that’s not how that goes, that’s not how dhrupad goes.” They might say to them, “Well, this is how we do it here, and you’re welcome to sing along with us.” Or they might say – and I definitely heard this from elder musicians in Trinidad and Guyana – “We sing it the traditional way, it’s Indians who have changed. We are maintaining the tradition.” One might smile when one hears these things, but there may also be a certain sense in which it is true; there are such things as marginal survivals, not just in Indian culture as well.

S.M.: Explain that term.

P.M.: Marginal survival… Well, some people don’t like the term, but it’s the idea that a diasporic group may go on perpetuating a tradition, maybe because they have an acute sense of “We must preserve this tradition,” while back in the host country, things change.

S.M.: You mean back in the home country?

P.M.: Yes, in the ancestral homeland. Is this why the duntal, which is this metal instrument that is so popular and ubiquitous in Guyana and Trinidad and Fiji, is hard to find in India? Was it popular there and then died out? It’s very curious. At the risk of digressing, you find this in other realms of Caribbean music as well. In Santería, the musical culture in Cuba, you find lots and lots of songs from West Africa – what’s now Nigeria – that probably came in the 19th century. Many of these songs probably have probably died out there by now. Scholars are verifying that. They go back to Nigeria and hear, “Oh that was an old song that we heard, that my grandmother used to sing;” this is when they hear some Cuban song. At any rate, there are such things that some people would call marginal survivals.

In the case of tan singing or local classical music, I think it’s more a question of them coming with a sort of fragmentary knowledge or garbled knowledge of certain aspects of North Indian classical music and reassembling these in a certain way with a certain amount of input from the records they’re getting in the ’20s and ’30s, not of classical music but perhaps of qawwali and ghazal and things like that. Then they have old 19th century or turn of the century song books of collections of song lyrics and they’re assembling these in their own way. And at a certain point, it becomes its own system; if they hear some sort of North Indian classical music from Ravi Shankar, for example – which, actually, they have very little occasion to hear – custodians of this tan singing system, might say, “Oh that’s boring music, our music is better than that, we don’t need that.”

S.M.: So, as the 20th century advances, what does urbanization, the development of wealth in the community, the development of class in the community, and so forth do to the music making, to performance, to the different aspects of the music?

P.M.: Yes, well, if we talk about Trinidad, a lot of things are going to get lost – and not just through urbanization and modernization. Knowledge of Hindi declines, so this whole folksong repertoire is declining dramatically. I was at Indo-Guyanese prayer and apprenticeship ceremony in Long Island in which a young man was being apprenticed to his spiritual guide, this pundit, and they did all these traditional songs and so on. And they did a mutteecore, which is a particular kind of women’s song session in which they do a little ritual off in the woods or some field. Nowadays you don’t have many people who can sing these songs anymore because they don’t know Hindi or Bhojpuri anymore. But, there are semi-professional women; there are these two women in their seventies and they are very feisty and funny and they know all these old songs, so they were there to sing along with this and to lead the others in singing.

S.M.: Okay, that’s relating to the decline of language. What about urbanization and modernization?

P.M.: Again, the grinding wheel songs and cane working songs and things like that are going to decline. There’s no doubt about it. But other things are going to be enlivened by it. When people have money they are going to have access to the mass media, whether it’s cassette recordings, or now CDs, the radio, TV; there could be a sort of cultural revival, especially in Trinidad, if we’re comparing with Guyana and Suriname. Trinidad has had a very lively musical scene with all kinds of music making. It’s a kind of middle-income country, not terribly poor; you know they have oil and ammonia and all that stuff, and it’s been a fairly open society, politically and culturally.

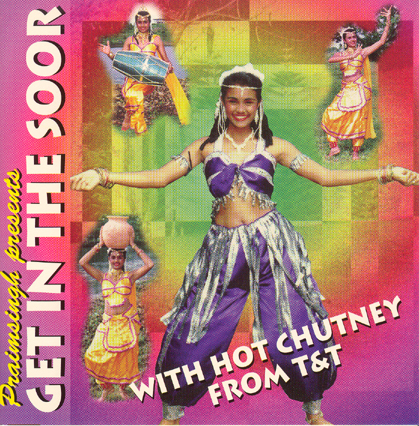

Indians have complained that they are discriminated against historically and so on, but in one way or another they have been able to preserve a lot of their culture or innovate new things. Plus they’ve had – perhaps because of their particular relationship with the Afro-Trinidadians – this real sense, especially since the ’70s, of cultural revival and that “We’ve got to promote our Indian culture.” This has stimulated a lot of musical activity, so while you have all this calypso and steel band and every possible kind of creole Afro-Trinidadian music making, you also have all these film song competitions, Chowtal competitions, and such on the Indian side. This traditional sort of tan singing, local classical music, sort of limps along, but there has been a lot of lively music and dance production. The most overt example of that is this whole Chutney phenomenon, which really flourishes in the ’70s and ’80s.

S.M.: Let’s get to that in a second. Since you brought up the political side, in Guyana, what did the Burnham years and the Burnham dictatorship do to the music and culture on the Indian side?

P.M.: Guyana is in some ways similar to Trinidad. You have the Afro-Caribbeans and the East Indians, the two big ethnic groups. Things became particularly different in the early ’60s when the British gave independence to the colonies in the West Indies, and things didn’t go so well in Guyana. There, as in Trinidad, the political parties formed along ethnic lines, so you’d have a Black party and an Indian party. In Guyana the person who was coming into power was this Cheddi Jagan, who was the leader of the Indian party. He was also a fervent anti-imperialist, and Washington, D.C. and the British didn’t like that, so basically he was ousted and this Forbes Burnham was put in, who was, at least rhetorically, a leftist – but in many ways he represented his own particular community. At any rate, there was ethnic discrimination against Indians, or at least they felt it existed. That was one thing, but probably more important was that he basically bankrupted the country. And we’re talking about the ’60s, ’70s, ’80s. He dies, but the party continues until the early nineties, and so there was very little production of any sort of commercial popular music, whether cassettes or records – mass media. Real cultural stagnation happened, and it’s terribly unfortunate. A lot of musicians, a lot of Guyanese left, both Black and Indian. It was just not a conducive atmosphere for musical innovation. So folksongs, Chowtal, things like that limped along, but it was really Trinidad that had a much more lively scene. That’s where, for example, this whole Chutney phenomenon really picked up in the ’70s and ’80s, really giving them and others the impression that they invented it, which is probably a bit of a misrepresentation.

S.M.: So let’s talk about Chutney. What is that?

P.M.: Ok, well, Chutney. Historically, this would be a music that has its roots in women’s folksongs, such as those that were sung as the mutteecore ceremony, or ritual, that I mentioned, or wedding songs – light, fast, rhythmic songs. Let’s say it might have its roots in some North Indian wedding song, sung in the Bhojpuri region at weddings. The men at various occasions are having their own fun drinking, dancing, singing their own songs; maybe they have some professional musicians. But at certain points in the wedding, the women, especially of the bride’s family, might sing various sorts of songs amongst themselves. And maybe one is playing the dholak – that’s the barrel drum – and they’re singing these fast songs in Bhojpuri Hindi sometimes with very spicy, ribald lyrics, making fun of the groom and even of his private parts; some of them would be very lewd and humorous. Women would also get up and dance. There are no men, around so they don’t have to worry about being blasphemous or shaming the family. It’s just women off perhaps in a field or in some house. We’re talking about farm communities, definitely, but they can also dance in a lively and sort of sexy style.

This tradition gets brought to the Caribbean and it definitely thrives in Guyana and Trinidad. At a certain point, certainly from the ’50s and ’60s, they started calling these songs in Suriname and Trinidad “Chutney,” which then comes the generic term for any sort of light, catchy, fast song, especially these women’s songs. What happens, in terms of its transformation into a pop genre, it’s not so much a musical development, but rather that it literally comes out of the closet, and that seems to have happened mostly in Trinidad in a series of stages, perhaps in the ’60s. These women are dancing in some hot and stuffy room at a Trinidadian wedding, and meanwhile outside there is a tent set up and the men in the neighborhood – well, the neighbors, maybe even some local Afro-Trinidadian people – are drinking, dancing, having fun, and the women are saying, “Why do we have to be stuck here in this room, all our friends and family are out there, why can’t we just go sing our songs out there?” And gradually it comes to be something that is done at weddings, perhaps with the women themselves playing the drums, or perhaps they bring some professional musicians, maybe men, who sing these same songs or songs in the same style, perhaps accompanying themselves again on the dholak, the duntow which is this metal rod, and the harmonium, which is this accordion-like instrument which is the most popular melodic instrument in North India as well as the Caribbean. So the singer is sitting on the ground, singing and accompanying himself on this little accordion-like keyboard with his right hand and pumping it with his left hand.

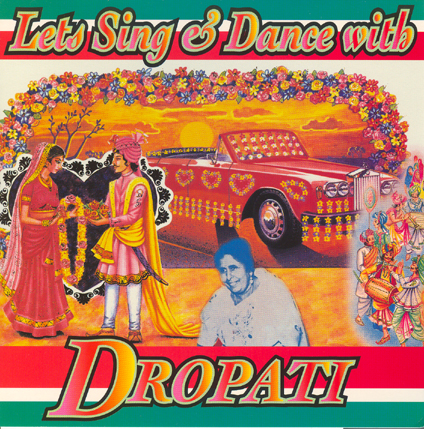

This then comes to be called Chutney at a certain point, and it seems to have started in Suriname where these folk traditions are particularly lively because the Surinamese still speak Hindi. I think it was in the early ’60s, someone produced a record of this elderly Surinamese woman named Dropati, singing these sorts of songs. That record spread around in Trinidad, and people liked it a lot even if they didn’t know any of the songs. But it somehow gave a sort of new incentive to popularize these songs. Then, in the 70’s I think some people organized a tour for Dropati. So, this music was sort of being recognized as something that can be performed in public.

In the ’80s, perhaps in response to popular demand, Trinidadian women and some men, are now used to doing this sort of thing at weddings – they are singing these songs, or you have a little group that sings them, and everyone dances around, maybe men with men, women with women, men with women, or just everyone in this crowded space doing it themselves, doing it together in their own way. The dance is a traditional Bhojpuri style of dancing. It’s derived from this Windham style, a lot of hips, but also these graceful hand and arm gestures, sort of like you might get in flamenco or Middle-Eastern dancing, and very bawdy and sexy. Which is funny, because it is a socially conservative community, but it’s this tradition that came straight out of the closet, and women could do these songs and be as sexy as they like; there’s no men around, and then taking it out of that context, into public.

Getting back to this next step that happens in the ’80s, they’re deciding, “Oh, we’re having so much fun dancing at these weddings. Why do we have to wait for the occasional wedding in the neighborhood? There isn’t another wedding for another two months. Why can’t we just have events, fêtes, where these are done?” And so, it was particularly one family of entrepreneurs that started holding these public Chutney dances. They would hire a band to come – band meaning, again, harmonium, dholak, duntal, and singer with a noisy PA system. And this would be in a big, open-air theater with some sort of covering because it rains a lot, and they would have a lot of plastic folding chairs and people sit and chat, and then when the music gets hot, they get up and dance. This was very controversial in the Indian community, because people said this was disgraceful: “our women should be upholding our traditional – they’re supposed to be our queens of the hearth,” and all that shame and honor. They’d say, “it’s okay for men to dance around, but for women to do this, this is unacceptable,” and this whole sort of polemic erupted in newspapers, talk shows, and so on. But basically the conservatives were shouted down, or danced down, and these Chutney fêtes became very popular. Every weekend you have them in Trinidad, and it’s spread now to Guyana, and there are Chutney clubs here in New York City as well. The next step was the sort of creolization of this music.

S.M.: So, as we get to that, we have been doing the classic thing of talking about this Indo-Caribbean – we’ve been doing the two cylinders, right, there’s the Indian cylinder and the Afro-Caribbean cylinder, which we haven’t been talking about. And of course, there’s a dynamic here, right? To what extent was Indo-Caribbean culture in the mid-20th century – or just as we come up to the period you’re discussing now – developing in isolation from Afro-Caribbean culture, and to what extent not?

P.M.: A lot of this development was very much in isolation. Let’s take Chowtal, which is this springtime folksong I described. It has nothing to do with creole, or Afro-Caribbean culture. Women’s folksongs, bhajans, film songs, this whole gamut of music is thoroughly hooked into India, whether it’s an ancestral tradition or whether it’s something that’s coming out of Bollywood. Of course, a lot of the Bollywood music is very Westernized, which is a whole other contradictory wrinkle in this whole situation. But we could mention tassa drumming, which I talked about a little bit. It’s this thunderously loud drum ensemble; these big heavy barrel drums called dhol, maybe three or four of them, these medium-sized drums called fuller — and they think that’s because it fills out the sound, it makes it more full. But in fact, it seems more likely that that term comes from Fula, which is a West African term. It is also a name that pops up here and there in the Caribbean as a kind of drum.

Then there is the tassa drum itself, or a couple of them. This is a little kettle drum, maybe about sixteen inches across and it hangs around your neck at about waist-level, and the player – there will be three or four of them perhaps – play them with these sticks. You can play these very fast rhythms – you know, brrrr-rat-tat-tat-tat-tat, these very fast rolls. This is purely out of Indian tradition. The whole ensemble is called tassa, and that particular drum is also called tassa. Or they call it “the cutter.” Why? Because it cuts through. But this is another situation like fuller, it seems like it probably comes from or at least was reinforced by kata, which is West African and Caribbean drum name. At any rate, what about the rhythms that they play on tassa? Many of them seem to come straight out of India. But then there are others that have names like dingolay or steel pan or whatever and that are clearly tassa versions of Afro-Caribbean music.

S.M.: So is it fair to say that, up to a certain point, the main area in which there might have been a sort of implicit conversation between the two communities musically was at the level of rhythm and percussion?

P.M.: Perhaps it might be. Now, keep in mind, if we focus on Trinidad, what are the big creole musics there? Calypso is a seasonal thing, and if we’re talking about the mid-20th century, or even nowadays, calypso is mostly a creole or Afro-Trinidadian thing. Indians have never been really that interested in participating in it, and perhaps not even listening to it, and very often they’re made fun of in the tradition in calypsos, even nowadays. So, that’s not really going to influence them musically that much. Then steel band is also mostly an Afro-Caribbean, Afro-Trinidadian thing. Not entirely, of course; perhaps the most famous steel band arranger in Trinidad nowadays, or for the last couple decades, is an Indian guy, and you have school bands and so on in which anyone can play and you certainly have East Indians that are adept at that. But mostly, and especially in its origins, it comes from lower class slums off the Port of Spain, Afro-Trinidadian communities.

S.M.: So there’s an urban and rural thing going on here as well, isn’t there?

P.M.: Yeah. We’re talking about the creole influence, such as it existed in East Indian Trinidadian music culture, which would not pertain to things like the famous genres of calypso and steel band which would be mostly Afro-Trinidadian things. Sure lots of East Indians, older ones that I interviewed in the ’90s, were crazy about Rudy Vallee and other popular American or Afro-American singers of the ’30s and ’40s, and some of them would even sing those songs. They had their ears open to things, but it didn’t necessarily become so much a part of their own music culture. So, what changed, and from where did these changes come? Although people look at sort of the pneumatic hip gyration and think that must have come from Afro-Trinidadian dancing, I don’t think that’s necessarily the case. You see plenty of that in Indian folk dancing. What changed was the idea that it was gradually considered acceptable to do this in public – men and women dancing together. I’m sure you would have Indian men and women in the ’50s, the ’60s, looking at Afro-Trinidadians dancing and having so much fun and thinking, “Gee, why can’t we do that too?”

And then the whole idea of having competitions; you have calypso competitions from, you know, the 1910s and ’20s. This caught on in Indian music-making in various ways: tan singing or local classical music competitions developed, and from the ’70s onward you have this big amateur song competition. It’s like American Idol and this is, you know, Indo-Trinidadian idol, and mostly singing film songs and so on; but very popular, very widespread, and originally patterned in structure and form on the calypso competitions.

S.M.: What about the reverse? Was there any injection of Indian material, or Indian rhythms, or Indian performative stuff or whatever into Afro-Trinidadian and Afro-Guyanese music?

P.M.: The biggest example of that would be in the realm of Soca. Some listeners will know something about the history of Soca. It really develops in the late ’70s. Lord Shorty, who is a calypso singer and is generally credited accurately with inventing the genre with some help, felt that Trinidad needed its own dance music the same way Jamaica did. Why should they always have to listen to reggae? (Calypso is not really a dance music, after all.) So he came up with this Soca rhythm in collaboration with another musician. And, of course, the Soca rhythm is going Dum-ch-dum-ch, Dum-ch-dum-ch. He himself was a sort of friend of East Indians, always had one ear tuned into East Indian culture. And he claimed that it was at least in part inspired by East Indian drumming. Now it’s hard to put one’s finger exactly on what he was referring to, but he was very explicit about this – and you certainly hear rhythms that are compatible. I mean, the most typical Indian and North Indian and Indo-Caribbean folk rhythm is something like doot-k-dit-k-dum, doot-k-dit-k-dum, which is certainly compatible, and they do all sorts of variations which might have inspired him to create this Soca rhythm.

And then of course, that takes on this whole life of its own and Soca becomes this hugely popular genre, and not just in Trinidad, but all over the Caribbean as well. And then what happens in the early ’90s, getting back to the Chutney side of things, Chutney is now a big and very popular phenomenon in the East Indian community, with Chutney dances and fêtes all over the place. And the music also creolizing to some extent, becoming performed more and more by what you could say dance bands, electrified instruments. Instead of playing harmonium you have someone playing synthesizer. And dholak, it’s hard to amplify it, so it was much easier to do it on a drum machine, and they could either imitate the dholak rhythm on a drum machine or play a Soca rhythm, you just press the Soca button. And then you have Dum-ch-dum-ch, Dum-ch-dum-ch, and singing the traditional Chutney melodies over this, and this is what came to be called Chutney Soca. Which is this now tremendously popular genre among Indo-Caribbeans, and also quite a few Afro-Caribbeans like it, or will dance to it. If you’re at club in Port of Spain, and they’re mostly putting on Beanie Man or Soca and then they put on a Chutney Soca, everyone will go on dancing to it if they are East Indian or black. It’s ironic that it was, at least according to Shorty, inspired by East Indian rhythms to begin with to some extent. But now they have sort of melded this way, and Chutney Soca is this very sort of natural blending of these two streams.

S.M.: And you mentioned the arrival of electronics, and drum machine, synthesizer and all of that; and I guess there’s always the dichotomy of that it always takes away from traditional instrumentation, but it also enables more and more people to be involved with the music, to hear it. It disseminates, right?

P.M.: Yeah, so as Chutney Soca becomes popular within the Indian community – this is mostly in the early 90’s – it was controversial. You would have traditional musicians who, first of all, liked local classical music more, and would be upset that every wedding, every party would turn into a Chutney fête with people dancing wildly and falling down. And the music, instead of being these sophisticated, more austere-sounding thumris and dhrupads now it was these simple and bouncy Chutney songs. At any rate, Chutney sort of took over the scene, both whether we’re talking about weddings or popular dances. But it would be in the ’80s and early ’90s mostly a classic ensemble of let’s say harmonium, dholak, duntaw. For whatever reasons, by the early 90’s this is being replaced by synthesizer, and, well, drum machine programmed into the synthesizer, maybe a duntal, but more of a sort of a band like that, perhaps with electric bass, maybe guitar. And it was controversial. Also, the singers are now singing more and more in English, because they run out of old Hindi words, they don’t understand Hindi anymore, or maybe they mix up Hindi and English. So you had a big argument in the Indian community that we’re losing our Indian tradition. At least with the old Chutney songs, we had base in traditional folk culture, but then other people are saying, “No, the music has to change. If you just go on doing the same old songs then young people won’t be interested.” So Chutney Soca is a way of keeping them interested in Indian culture in a modernized fashion. I think there is much to be said for that point of view.

And so what is Chutney Soca now? It is usually a typical Indian – and specifically Bhojpuri-style – melody, a lot of which are really simple. I mean, this is not like a Ravi Shankar improvisation on sitar. These are very simple melodies, nowadays sung in English or a little bit of Hindi, sometimes singing little vignettes about Indian social life. And so, often instead of the very traditional Indian style rhythm that you would hear on the dholak, which would be doot-k-dit-k-dum, doot-k-dit-k-dum, instead you hear Dum-ch-dum-ch, Dum-ch-dum-ch, which is more the Soca rhythm. So, as with any musical innovation, you have people who like it or don’t like it, but young people certainly love it. It’s very popular in clubs; people like to dance to it. And people will come dance any style they like; it might look like Soca dancing, but again, sometimes, as far as I’m concerned – and I’m not the only one – the best dancers are the old women because they can do it in this very lively, and you could even say sexy, Indian folk style.

S.M.: So – this is a huge change of topic, but a very important one – there’s a huge double diaspora, right? Situate for me the role that New York City, and also Toronto, perhaps in this musical trajectory. I mean, the Guyanese and Trinidadian communities here are enormous, aren’t they? And they’re probably quite significant as a percentage of the total number of Guyanese and Trinidadians, both Afro- and Indo- that are anywhere in the world. What’s going on here in New York vis-à-vis these musics?

P.M.: Well certainly there’s a very lively production scene. There are commercial recordings, although I would say it’s not such a recording-based, or recording-driven music as reggae or dancehall reggae is. But certainly on Liberty Avenue in Queens you can find plenty of stores with modern CDs and so on produced here in New York City. I’m sure there’s more production that goes on here than you would find in Guyana.

S.M.: Do people come from Guyana and Trinidad to record and make their musical professional life in New York?

P.M.: Certainly if a Guyanese wants to record, yeah, I don’t think there’s much happening in Guyana unless things have changed in the last few years when, in the 90’s there was nothing happening at all, and I think it’s been slow to change. Trinidad would have some recording studios. But certainly there’s a circuit now, and musicians are cycling back and forth between let’s say Trinidad, New York City, Toronto, even Miami. I know some musicians who are constantly traveling back and forth. You might say because there is a finite audience in each one of those places, but the musicians and their accompanists keep rotating and going back and forth, you have festivals in one place or another. So certainly there is a lively scene. I’m not sure if there are particular developments that are happening here that are not happening elsewhere – for example Trinidad. Certainly you have collaborations; you might have a dancehall reggae singer with an Indo-Trinidadian musician. There are various sorts of fusions like that. And you have a lot of young Indo-Trinidadians and Indo-Guyanese who are very tuned into dancehall and do their own versions of that. Sometimes with Indian rhythms or whatever, sort of self-conscious fusions. People are very cosmopolitan and open-minded in that way.

S.M.: So is there a New York style, or a New York approach to making Indo-Caribbean music? Whether at the level of the classical forms or the level of the pop stuff?

P.M.: Not that I know of. I don’t think so, unless something’s happening just very recently.

S.M.: And it is a similar situation in Toronto? Is New York really the epicenter for these communities, outside of their actual countries of origin?

P.M.: I think Toronto is a pretty lively scene. I went up there about ten years ago and they had their own host of local classical musicians, both Trinidadians and Guyanese, some Chutney clubs, that sort of thing. Very similar, maybe a little bit smaller.

S.M.: You made passing references to people you know here, events that you go to here, the event on Long Island that you were describing just now. So is there an economy, an immigrant economy? Does it support or sustain some population of musician through these events, through weddings and other ceremonies, through club performances and all that kind of thing?

P.M.: Yeah, and that has grown a lot. I mean, when I started going to Trinidad and Guyana in the early ’90s, this whole Chutney scene was really just getting off the ground. I mean I have cassettes where the people who would subsequently become stars are singing ads for the Tire King and Stag Beer, and these guys have day jobs; they are policemen or whatever. As of the late ’90s, the music had gotten so popular that they had quit their day jobs, they were full time Chutney singers, they were touring around Trinidad, Guyana, New York, Miami, Toronto, whatever circuit. So that scene has really become much more remunerative and self-sustaining. Meanwhile these amateur song competitions which are patronized by East Indian businesses were a big thing.

Even in the realm of traditional music this is happening. One of my closest friends and informants in the Indo-Guyanese community here, a very brilliant drummer named Rudy Sakes Narayan, used to work in a hospital. He injured his back – this would have been at least six or eight years ago – and was unable to work. This was clearly a setback, but in the mean time he has found himself constantly in demand as a dholak player because he is a virtuoso. Not necessarily in this pop-Chutney scene at all but rather for pujas – that is, prayer sessions, weddings, different sorts of contexts in which they want traditional music, and so they will have singers as well. He has a reputation as a very knowledgeable and skilled drummer. He’s a young guy, maybe 40 or so, and he is constantly flying down to Guyana or Curaçao, or even Los Angeles or Toronto. Wherever you have these pockets of Indian communities, they will hire him to come and drum at a wedding.

So I don’t want to say it’s a wealthy community but it’s not completely impoverished either; they are sort of working class. Yes, some of these traditions are declining, but you have a lot of interest in maintaining religion, and to do that properly you have these day-long prayer sessions, what would be called a puja, and a lot of that is the pundit holding forth for hours with people sitting under a tent, but then it should turn into a song session. There should be traditional music for that of one sort or another. You can have just some local person who can play a little bit on the drum, but if you want to do it properly, you spend some money and you get a really good drummer. So there there is a circuit of musicians, and some of them are real virtuosos.

Credit: https://afropop.org/articles/peter-manuel-on-indo-caribbean-music

Please consider Donating to keep our culture alive

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.