It’s a familiar scene for many Indo-Caribbeans: a family gathering—whether it be of celebration or mourning—is inconsequential. Each body, whether belonging to an aging ajee or a wide eyed bacha, is adorned in their best threads. Tikkas are unsmudged, though the men have long untucked their dress shirts, one hand choking a glass of rum, their wives hustling to plate their food. Tangled amongst shouts of laughter and hushed whispers are sound waves belonging to a guitar, tabla, and harmonium. A voice cuts through the instrumental to sing a narrative orbiting around love, rum, and bacchanal. Someone’s cha cha hears the familiar tune and cries for the volume to be turned up. As always, the music will be the last thing put away once the guests return to their homes.

Like many communities across the world, the Indo-Caribbean community has developed a very intimate and nuanced relationship with music. From chowtal to chutney-soca, Indo-Caribbean artists have stitched together lyrics and instrumentals that preserve what remains of their ties to the subcontinent while also acknowledging the context with which these remnants have become creolized. What stands to remain is a repertoire of songs that both elegize and eulogize a crossroads of culture that remembers what was, celebrates what is, and mourns for what could have been.

Folksongs and the “Mythic” India

As with many great cultural legacies, Indo-Caribbean music began with women. Specifically, it harkens back to the songs the indentured laborers would sing during various occasions. As Peter Manuel highlights in his article, Indo-Caribbean Music Enters the New Millennium, whether it was in the sugarcane fields or during Phagwa celebrations, women offered their voices as East Indians distinguished their culture within the Caribbean. Manuel describes the legacy of these women as “the largest and most extensively cultivated body of music

bequeathed by indentured laborers” (p.152).

In an earlier article, Music, Identity, and Images of India in the Indo-Caribbean Diaspora, Manuel explains that “music came to play a particularly important role in sustaining Indian culture and ties to India itself” (p.19). For a culture that has always struggled with a lack of direct contact with its ancestral land, music became a significant tool for building and maintaining a bridge between India and the Caribbean. It allowed for the preservation of traditional Indian instruments, such as the harmonium, dholak, and dandtal, the latter which can be described as “an archaic Bhojpuri-region instrument which, for whatever reasons, became ubiquitous in the Caribbean” (p. 20). Beyond familiar sounds that evoked comforting and celebrated images of Mother India, early Indo-Carribean music played a crucial role in preserving the use of Bhojpuri or Hindi, common languages shared amongst the indentured population. As other markers of the community’s “Indianess” began to fall away (i.e. caste consciousness), primarily because of their lack of value in their new environment, the desire to hold onto their beloved homeland was crucial for the East Indians. It’s important to note that many of the earlier songs favored by the Indo-Caribbean community often spoke of “peacocks, elephants, and the sacred geography of Brindavan, Lanka, and the Ganges,” all belonging to a deeply missed, exceptionally idealized, India (p. 19). These songs in particular were performed in a genre unique to the Indo-Caribbean culture known as tan-singing, which combined classical and semi-classical genres of North Indian music.

“Oh Rani, I want to marry Hindustani:” The Climb of Chutney-Soca

So, how does a culture’s musical identity shift from perpetuating a romanticized image of the subcontinent to songs such as Baron’s Raja Rani? As the East Indians deepened their roots in the rich soil of the Caribbean, the blend of Indian, African, Portuguese, and Chinese cultures often associated with the Caribbean landscape began to shape. This, paired with the abolition of indentured servitude in the early twentieth century, allowed for the Indo-Caribbean community to explore what the fabric of their culture would look like, which included music.

It would take several decades post liberation, but by the late 1960s, Sundar Popo would make his musical debut. Born on the islands of Trindad and Tobago, Sundar Popo debuted with his song titled Nani and Nana, which details the life goings of both a paternal and maternal grandmother. While it can be assumed that Sundar Popo pulled inspiration from the lives of his own grandmothers, the lyrics of the song—penned and performed in Trinidadian Hindustani and Trinidadian Creolese—applied to the beloved grandmothers of so many Indo-Trinidadians that the song quickly became beloved by the community of the twin islands, and eventually spread across the entire Indo-Carribean community.

Sundar Popo is often credited for fathering the groundwork for what would later evolve into the popularized chutney-soca, also known as Indian soca. However, a Trini artist preceding Sundar Popo, Lord Shorty, played an equally significant role in providing the blueprint of the genre. The Carribean as a whole, much like the rest of the world, was undergoing immense cultural shifts during the 1960s. For Lord Shorty, the one that brought the greatest grievance was the potential for traditional calypso to be replaced by what he called “Yankee boogaloo,” according to his wife Claudette Blackman. This catapulted Lord Shorty on a musical journey that would prompt him to bring together the stylings of calypso music with reference to Indian rhythms and expressions, as seen in songs such as Om Shanti Om. This decision was highly influenced by the fact that the artist had grown up in Lengua, a predominantly East Indian village. Though much of the calypso community approached Lord Shorty’s musical experimentation with hesitation, his stylings eventually proved to be successful.

Lord Shorty’s celebration of East Indian culture would foreshadow an interesting trend amongst Afro-Carribean musicians. It became commonplace for Afro-Carribeans to celebrate East Indian women of the Carribean, as noted in Baron’s Raja Rani referenced earlier. However, their Indo-Carribean counterparts prioritized the image of East Indian women as being unfaithful, manipulative, and unvirtuous, as noted by Nishi Malhotra.

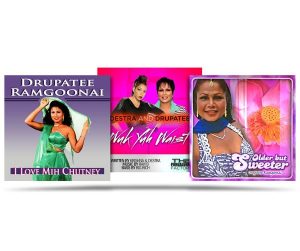

The misogyny of the Indo-Carribean music scene would reach a boiling point with the chutney-soca debut of Drupatee Ramgoonai in 1987. As Malhotra notes, “while it was considered acceptable for East Indian men to poke fun at ‘their’ women, an Indian woman who dared to sing Calypso was said to be bringing disgrace to the community.” However, the critics were inconsequential to Ramgoonai and her success, who would go on to release chutney-soca favorites such as Indian Gyal and Mr. Bissesar—also known as Roll Up De Tassa—and would later be featured on the track Real Unity for the film soundtrack of Bazodee, alongside artists such as Machel Montano, Major Lazer, and Shaggy.

“How many times do I have to tell people that I am not Indian? Or that I am Indian but from somewhere else.”

Perhaps these words, pulled from Rajiv Mohabir’s 2017 essay “Minority” Identity Development Model For An Indo-Caribbean American in Five Stages, can be most clearly understood when listening to chutney-soca music. The genre’s East Indian references blend beautifully with Afro beats, illustrating the “somewhere else” with which the “Indianess” of Indo-Caribbeans inhabits. With the desire to perfectly preserve their ancestral culture no longer at the forefront of their work, Indo-Carribean artists have the freedom to define, respond to, and evolve their culture in the context that it stands in today.

Donate

Please consider Donating to keep our culture alive

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.